Webb probes Messier 82 (M82), an extreme starburst galaxy

Amid a galaxy teeming with new and young stars lies an intricate substructure

The north and east compass arrows show the orientation of the image on the sky. Note that the relationship between north and east on the sky (as seen from below) is flipped relative to direction arrows on a map of the ground (as seen from above).

The scale bar is labelled in light-years.

This image shows invisible near-infrared wavelengths of light that have been translated into visible-light colours. The colour key shows which NIRCam filters were used when collecting the light. The colour of each filter name is the visible light colour used to represent the infrared light that passes through that filter.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, A. Bolatto (UMD)

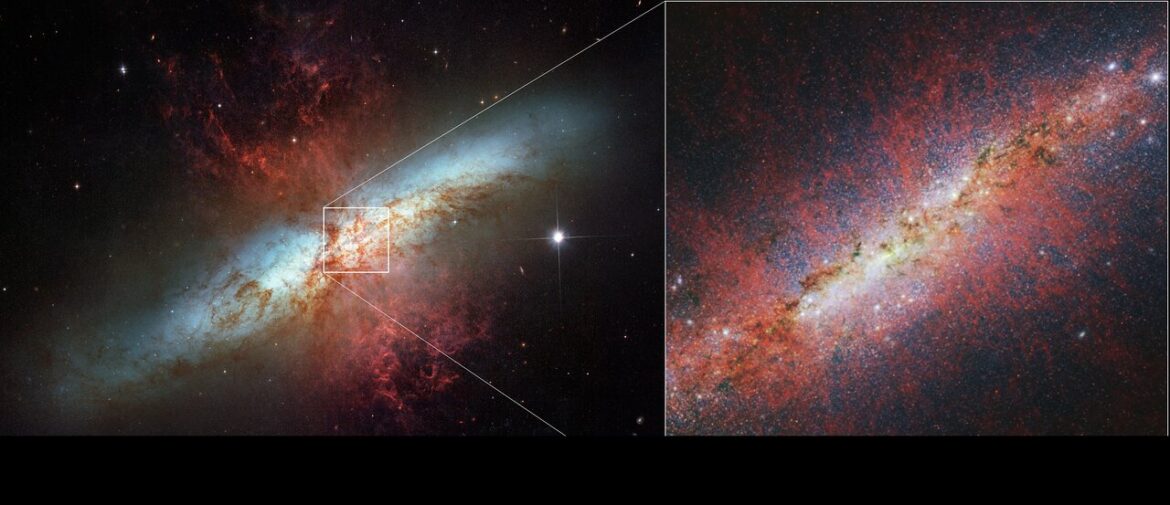

The NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope has set its sights on the starburst galaxy Messier 82 (M82), a small but mighty environment that features rapid star formation. By looking closer with Webb’s sensitive infrared capabilities, a team of scientists is getting to the very core of the galaxy, gaining a better understanding of how it is forming stars and how this extreme activity is affecting the galaxy as a whole.

An international team of astronomers has used the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope to survey the starburst galaxy Messier 82 (M82). Located 12 million light-years away in the constellation Ursa Major, this galaxy is relatively compact in size but hosts a frenzy of star formation activity. For comparison, M82 is sprouting new stars 10 times faster than the Milky Way galaxy.

The team directed Webb’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) instrument toward the starburst galaxy’s centre, obtaining a closer look at the physical conditions that foster the formation of new stars.

“M82 has garnered a variety of observations over the years because it can be considered as the prototypical starburst galaxy,” said Alberto Bolatto, lead author of the study. “Both Spitzer and Hubble space telescopes have observed this target. With Webb’s size and resolution, we can look at this star-forming galaxy and see all of this beautiful new detail.”

Star formation continues to maintain a sense of mystery because it is shrouded by curtains of dust and gas, creating an obstacle to observing this process. Fortunately, Webb’s ability to peer in the infrared is an asset in navigating these murky conditions. Additionally, these NIRCam images of the very centre of the starburst were obtained using an instrument mode that prevented the very bright source from overwhelming the detector.

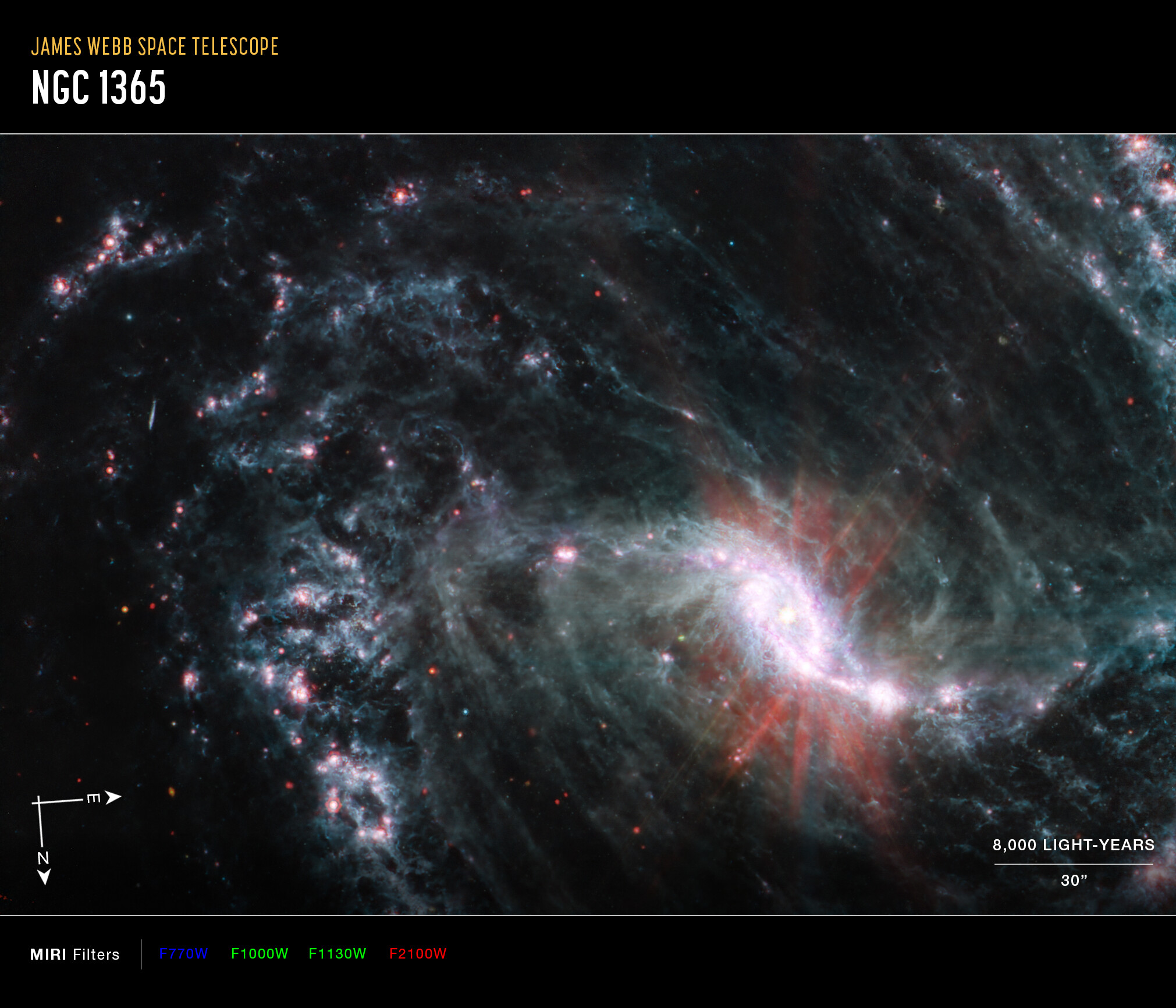

This image from Webb’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) instrument shows M82’s galactic wind via emission from sooty chemical molecules known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). PAHs are very small dust grains that survive in cooler temperatures but are destroyed in hot conditions. The structure of the emission resembles that of hot, ionised gas, suggesting PAHs may be replenished by continued ionisation of molecular gas.

In this image, light at 3.35 microns is coloured red, 2.50 microns is green, and 1.64 microns is blue (filters F335M, F250M, and F164N, respectively).

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, A. Bolatto (UMD)

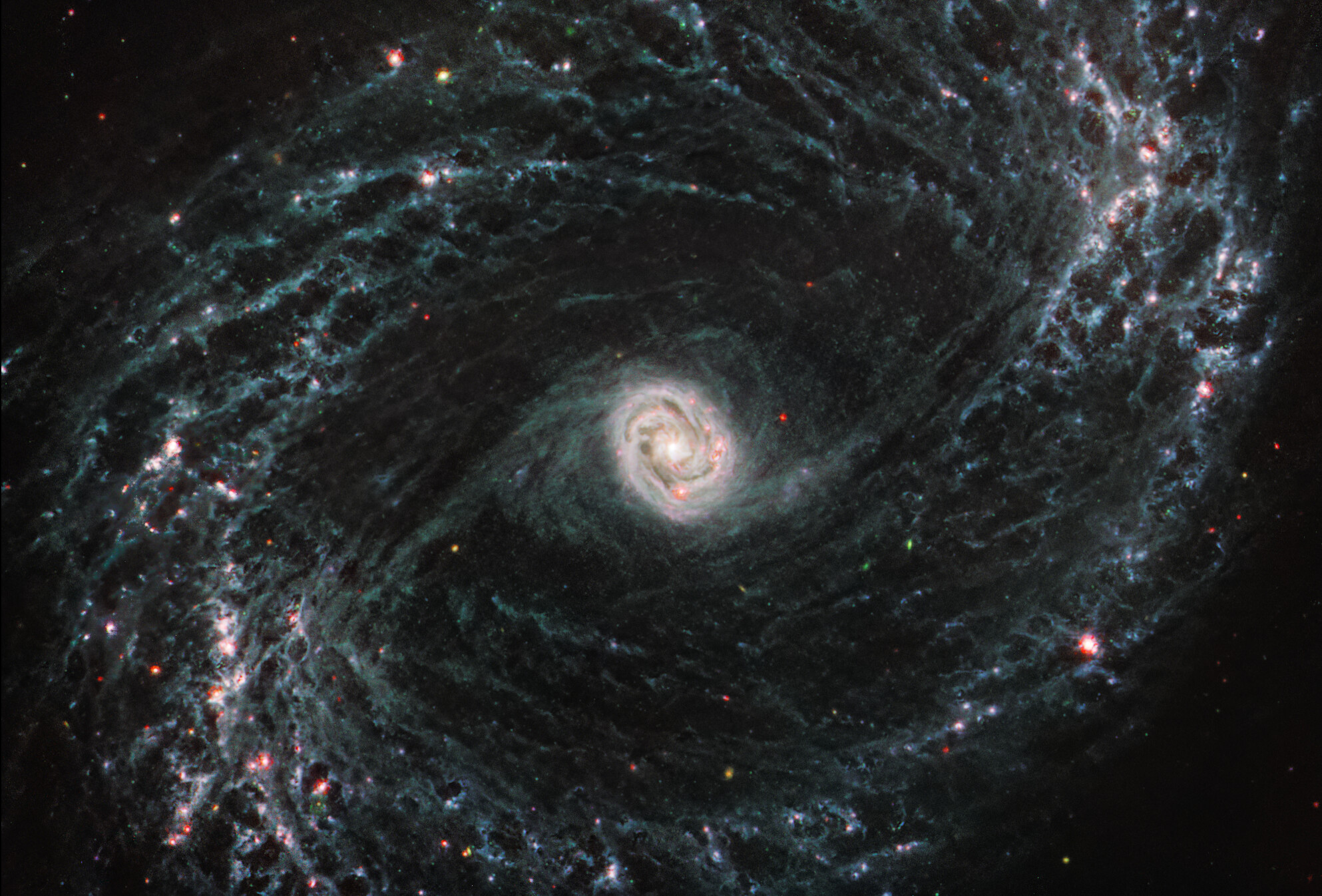

While dark brown tendrils of dust are threaded throughout M82’s glowing white core even in this infrared view, Webb’s NIRCam has revealed a level of detail that has historically been obscured. Looking closer toward the centre, small specks depicted in green denote concentrated areas of iron, most of which are supernova remnants. Small patches that appear red signify regions where molecular hydrogen is being lit up by the radiation from a nearby young star.

“This image shows the power of Webb,” said Rebecca Levy, second author of the study, at the University of Arizona in Tucson. “Every single white dot in this image is either a star or a star cluster. We can start to distinguish all of these tiny point sources, which enables us to acquire an accurate count of all the star clusters in this galaxy.”

Looking at M82 in slightly longer infrared wavelengths, clumpy tendrils represented in red can be seen extending above and below the plane of the galaxy. These gaseous streamers are a galactic wind rushing out from the core of the starburst.

One area of focus for this research team was understanding how this galactic wind, which is caused by the rapid rate of star formation and subsequent supernovae, is being launched and influencing its surrounding environment. By resolving a central section of M82, scientists have been able to examine where the wind originates, and gain insight into how hot and cold components interact within the wind.

This image from Webb’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) instrument shows the centre of M82 with an unprecedented level of detail. With Webb’s resolution, astronomers can distinguish small, bright compact sources that are either individual stars or star clusters. Obtaining an accurate count of the stars and clusters that compose M82’s centre can help astronomers understand the different phases of star formation and the timelines for each stage.

In this image, light at 2.12 microns is coloured red, 1.64 microns is green, and 1.40 microns is blue (filters F212N, 164N, and F140M, respectively).

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, A. Bolatto (UMD)

Webb’s NIRCam instrument was well suited to tracing the structure of the galactic wind via emission from sooty chemical molecules known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). PAHs can be considered as very small dust grains that survive in cooler temperatures but are destroyed in hot conditions.

Much to the team’s surprise, Webb’s view of the PAH emission highlights the galactic wind’s fine structure — an aspect previously unknown. Depicted as red filaments, the emission extends away from the central region where the heart of star formation is located. Another unanticipated find was the similarity between the structure of the PAH emission and that of the hot, ionised gas.

“It was unexpected to see the PAH emission resemble ionised gas,” said Bolatto. “PAHs are not supposed to live very long when exposed to such a strong radiation field, so perhaps they are being replenished all the time. It challenges our theories and shows us that further investigation is required.”

Webb’s observations of M82 in near-infrared light also spur further questions about star formation, some of which the team hopes to answer with additional data gathered with Webb, including that of another starburst galaxy. Two other papers from this team characterising the stellar clusters and correlations among wind components of M82 are almost finalised.

The Webb image is from the telescope’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) instrument. The red filaments trace the shape of the cool component of the galactic wind via polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). PAHs are very small dust grains that survive in cooler temperatures but are destroyed in hot conditions. The structure of the emission is similar to that of the ionised gas, suggesting PAHs may be replenished from cooler molecular material as it is ionised.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, A. Bolatto (UMD)

In the near future, the team will have spectroscopic observations of M82 from Webb ready for their analysis, as well as complementary large-scale images of the galaxy and its wind. Spectral data will help astronomers determine accurate ages for the star clusters and provide a sense of how long each phase of star formation lasts in a starburst galaxy environment. On a broader scale, inspecting the activity in galaxies like M82 can deepen astronomers’ understanding of the early Universe.

“With these amazing Webb images, and our upcoming spectra, we can study how exactly the strong winds and shock fronts from young stars and supernovae can remove the very gas and dust from which new stars are forming,” said Torsten Böker of the European Space Agency, a co-author of the study. “A detailed understanding of this ‘feedback’ cycle is important for theories of how the early Universe evolved, because compact starbursts such as the one in M82 were very common at high redshift.”

These findings have been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

Press release from ESA Webb.

![Webb looks for Fomalhaut’s asteroid belt and finds much more Webb asteroid belt Fomalhaut’s The NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and ESA's Herschel Space Observatory, as well as the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), have previously taken sharp images of the outermost belt. However, none of them found any structure interior to it. [Image description: An orange oval extends from the 1 o’clock to 7 o’clock positions. It features a prominent outer ring, a darker gap, an intermediate ring, a narrower dark gap, and a bright inner disc. At the centre is a ragged black spot indicating a lack of data.] Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, A. Pagan (STScI), A. Gáspár (University of Arizona)](https://scientificult.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/weic2312a-1024x916.jpg)