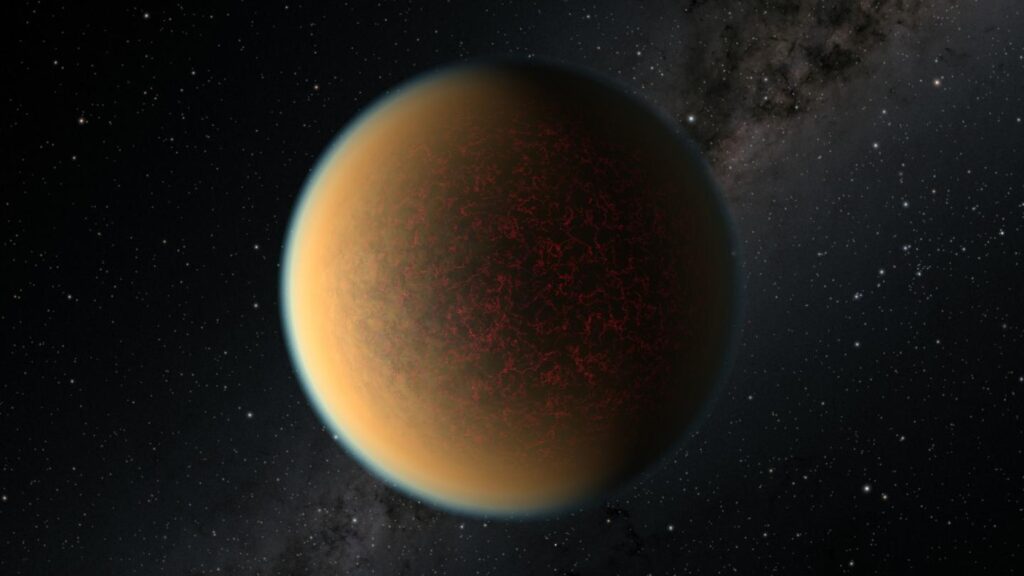

Hubble sees new atmosphere forming on a rocky exoplanet, GJ 1132 b

The planet GJ 1132 b appears to have begun life as a gaseous world with a thick blanket of atmosphere. Starting out at several times the radius of Earth, this so-called “sub-Neptune” quickly lost its primordial hydrogen and helium atmosphere, which was stripped away by the intense radiation from its hot, young star. In a short period of time, it was reduced to a bare core about the size of Earth.

To the surprise of astronomers, new observations from Hubble [1] have uncovered a secondary atmosphere that has replaced the planet’s first atmosphere. It is rich in hydrogen, hydrogen cyanide, methane and ammonia, and also has a hydrocarbon haze. Astronomers theorise that hydrogen from the original atmosphere was absorbed into the planet’s molten magma mantle and is now being slowly released by volcanism to form a new atmosphere. This second atmosphere, which continues to leak away into space, is continually being replenished from the reservoir of hydrogen in the mantle’s magma.

“This second atmosphere comes from the surface and interior of the planet, and so it is a window onto the geology of another world,” explained team member Paul Rimmer of the University of Cambridge, UK. “A lot more work needs to be done to properly look through it, but the discovery of this window is of great importance.”

ESA/Hubble, Digitized Sky Survey 2, CC BY 4.0.

Acknowledgement: Davide De Martin

“We first thought that these highly radiated planets would be pretty boring because we believed that they lost their atmospheres,” said team member Raissa Estrela of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, California, USA. But we looked at existing observations of this planet with Hubble and realised that there is an atmosphere there.”

“How many terrestrial planets don’t begin as terrestrials? Some may start as sub-Neptunes, and they become terrestrials through a mechanism whereby light evaporates the primordial atmosphere. This process works early in a planet’s life, when the star is hotter,” said team leader Mark Swain of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “Then the star cools down and the planet’s just sitting there. So you’ve got this mechanism that can cook off the atmosphere in the first 100 million years, and then things settle down. And if you can regenerate the atmosphere, maybe you can keep it.”

In some ways, GJ 1132 b has various parallels to Earth, but in some ways it is also very different. Both have similar densities, similar sizes, and similar ages, being about 4.5 billion years old. Both started with a hydrogen-dominated atmosphere, and both were hot before they cooled down. The team’s work even suggests that GJ 1132 b and Earth have similar atmospheric pressure at the surface.

NASA, ESA, and P. Jeffries (STScI)

However, the planets’ formation histories are profoundly different. Earth is not believed to be the surviving core of a sub-Neptune. And Earth orbits at a comfortable distance from our yellow dwarf Sun. GJ 1132 b is so close to its host red dwarf star that it completes an orbit the star once every day and a half. This extremely close proximity keeps GJ 1132 b tidally locked, showing the same face to its star at all times — just as our moon keeps one hemisphere permanently facing Earth.

“The question is, what is keeping the mantle hot enough to remain liquid and power volcanism?” asked Swain. “This system is special because it has the opportunity for quite a lot of tidal heating.”

The phenomenon of tidal heating occurs through friction, when energy from a planet’s orbit and rotation is dispersed as heat inside the planet. GJ 1132 b is in an elliptical orbit, and the tidal forces acting on it are strongest when it is closest to or farthest from its host star. At least one other planet in the host star’s system also exerts a gravitational pull on the planet. The consequences are that the planet is squeezed or stretched by this gravitational “pumping.” That tidal heating keeps the mantle liquid for a long time. A nearby example in our own Solar System is the Jovian moon, Io, which has continuous volcanism as a result of a tidal tug-of-war between Jupiter and the neighbouring Jovian moons.

The team believes the crust of GJ 1132 b is extremely thin, perhaps only hundreds of feet thick. That’s much too feeble to support anything resembling volcanic mountains. Its flat terrain may also be cracked like an eggshell by tidal flexing. Hydrogen and other gases could be released through such cracks.

“This atmosphere, if it’s thin — meaning if it has a surface pressure similar to Earth — probably means you can see right down to the ground at infrared wavelengths. That means that if astronomers use the James Webb Space Telescope to observe this planet, there’s a possibility that they will see not the spectrum of the atmosphere, but rather the spectrum of the surface,” explained Swain. “And if there are magma pools or volcanism going on, those areas will be hotter. That will generate more emission, and so they’ll potentially be looking at the actual geological activity — which is exciting!”

This result is significant because it gives exoplanet scientists a way to figure out something about a planet’s geology from its atmosphere,” added Rimmer. “It is also important for understanding where the rocky planets in our own Solar System — Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars, fit into the bigger picture of comparative planetology, in terms of the availability of hydrogen versus oxygen in the atmosphere.”

###

Notes:

[1] The observations were conducted as part of the Hubble observing program #14758 (PI: Zach Berta-Thomson).