Rare Fossil Teeth from China Overturn Long-held Views about Evolution of Vertebrates

An international team of researchers has discovered 439-million-year-old remains of a toothed fish that suggest the ancestors of modern osteichthyans (ray- and lobe-finned fish) and chondrichthyans (sharks and rays) originated much earlier than previously thought.

Related findings were published in Nature on Sept. 28.

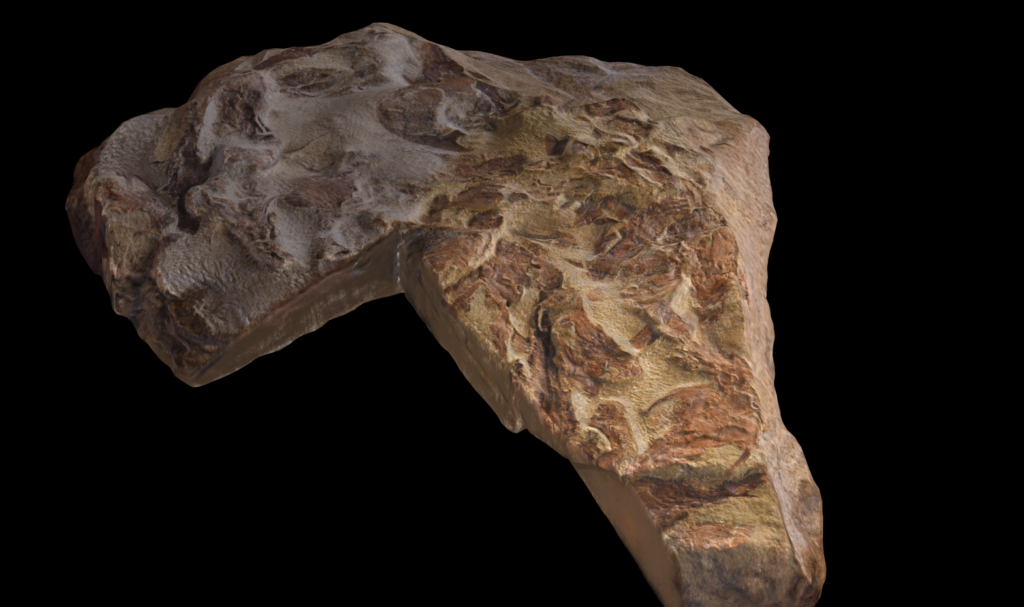

A remote site in Guizhou Province of south China, containing sequences of sedimentary layers from the distant Silurian period (around 445 to 420 million years ago), has produced spectacular fossil finds, including isolated teeth identified as belonging to a new species (Qianodus duplicis) of primitive jawed vertebrate. Named after the ancient name for modern-day Guizhou, Qianodus possessed peculiar spiral-like dental elements carrying multiple generations of teeth that were added throughout the life of the animal.

The tooth spirals (or whorls) of Qianodus turned out to be one of the least common fossils recovered from the site. They are small elements that rarely reach 2.5 mm and as such had to be studied under magnification with visible light and X-ray radiation.

A conspicuous feature of the whorls is that they contained a pair of teeth rows set into a raised medial area of the whorl base. These so-called primary teeth show an incremental increase in size towards the inner (lingual) portion of the whorl. What makes the whorls of Qianodus unusual in comparison with those of other vertebrates is the clear offset between the two primary teeth rows. A similar arrangement of neighboring teeth rows is also seen in the dentitions of some modern sharks but has not been previously identified in the tooth whorls of fossil species.

The discovery indicates that the well-known jawed vertebrate groups from the so-called “Age of Fishes” (420 to 460 million years ago) were already established some 20 million years earlier.

“Qianodus provides us with the first tangible evidence for teeth, and by extension jaws, from this critical early period of vertebrate evolution,” said LI Qiang from Qujing Normal University.

Unlike the continuously shedding teeth of modern sharks, the researchers believe that the tooth whorls of Qianodus were kept in the mouth and increased in size as the animal grew. This interpretation explains the gradual enlargement of replacement teeth and the widening of the whorl base as a response to the continuous increase in jaw size during development.

For the researchers, the key to reconstructing the growth of the whorls was two specimens at an early stage of formation, easily identified by their noticeably smaller sizes and fewer teeth. A comparison with the more numerous mature whorls provided the palaeontologists with a rare insight into the developmental mechanics of early vertebrate dentitions. These observations suggest that primary teeth were the first to form whereas the addition of the lateral (accessory) whorl teeth occurred later in development.

“Despite their peculiarities, tooth whorls have, in fact, been reported in many extinct chondrichthyan and osteichthyan lineages,”said Plamen Andreev, the lead author of the study. “Some of the early chondrichthyans even built their dentition entirely from closely spaced whorls.”

The researchers claim that this was also the case for Qianodus. They made this conclusion after examining the small (1–2 mm long) whorls of the new species with synchrotron radiation—a CT scanning process that uses high energy X-rays from a particle accelerator.

“We were astonished to discover that the tooth rows of the whorls have a clear left or right offset, which indicates positions on opposing jaw rami,” said Prof. ZHU Min from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

These observations are supported by a phylogenetic tree that identifies Qianodus as a close relative to extinct chondrichthyan groups with whorl-based dentitions.

“Our revised timeline for the origin of the major groups of jawed vertebrates agrees with the view that their initial diversification occurred in the early Silurian,” said Prof. ZHU.

The discovery of Qianodus provides tangible proof for the existence of toothed vertebrates and shark-like dentition patterning tens of millions of years earlier than previously thought. The phylogenetic analysis presented in the study identifies Qianodus as a primitive chondrichthyan, implying that jawed fish were already quite diverse in the Lower Silurian and appeared shortly after the evolution of skeletal mineralization in ancestral lineages of jawless vertebrates.

“This puts into question the current evolutionary models for the emergence of key vertebrate innovations such as teeth, jaws, and paired appendages,” said Ivan Sansom, a co-author of the study from the University of Birmingham.

Press release from the Chinese Academy of Sciences about the fossil teeth overturning long-held views on the evolution of vertebrates