Hubble watches spoke season on Saturn

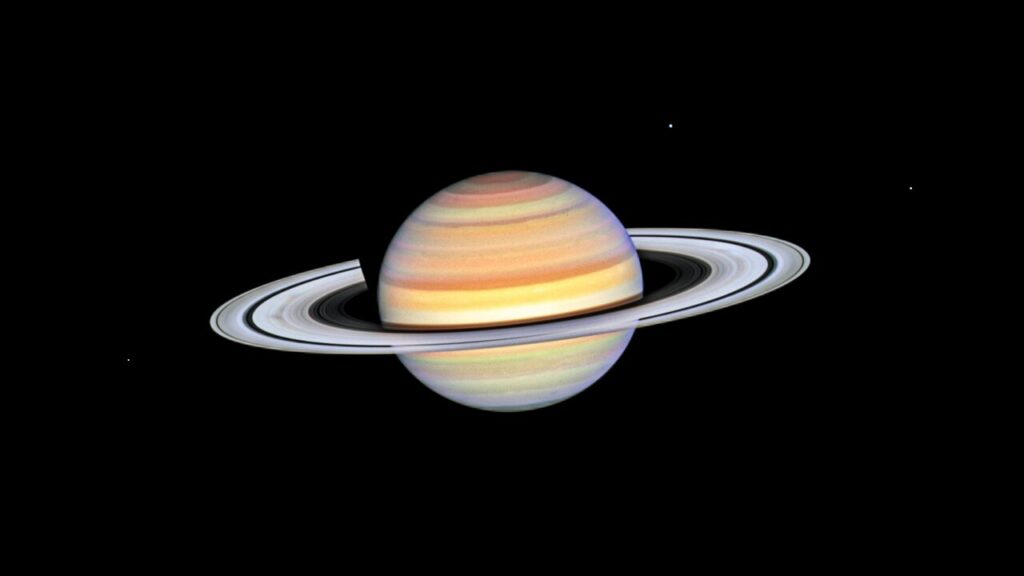

Saturn’s spokes are transient features that rotate along with the rings. Their ghostly appearance only persists for two or three rotations around Saturn. During active periods, freshly-formed spokes continuously add to the pattern.

In 1981, NASA’s Voyager 2 first photographed the ring spokes. Hubble continues observing Saturn annually as the spokes come and go. This cycle has been captured by Hubble’s Outer Planets Atmospheres Legacy (OPAL) program that began nearly a decade ago to annually monitor weather changes on all four gas-giant outer planets.

Hubble’s crisp images show that the frequency of spoke apparitions is seasonally driven, first appearing in OPAL data in 2021 but only on the morning (left) side of the rings. Long-term monitoring shows that both the number and contrast of the spokes vary with Saturn’s seasons. Saturn is tilted on its axis like Earth and has seasons lasting approximately seven years.

This year, these ephemeral structures appear on both sides of the planet simultaneously as they spin around the giant world. Although they look small compared with Saturn, their length and width can stretch longer than Earth’s diameter!

The OPAL team notes that the leading theory is that spokes are tied to interactions between Saturn’s powerful magnetic field and the sun. Planetary scientists think that electrostatic forces generated from this interaction levitate dust or ice above the ring to form the spokes, though after several decades no theory perfectly predicts the spokes. Continued Hubble observations may eventually help solve the mystery.

Credit: Credit: NASA, ESA, STScI, A. Simon (NASA-GSFC)

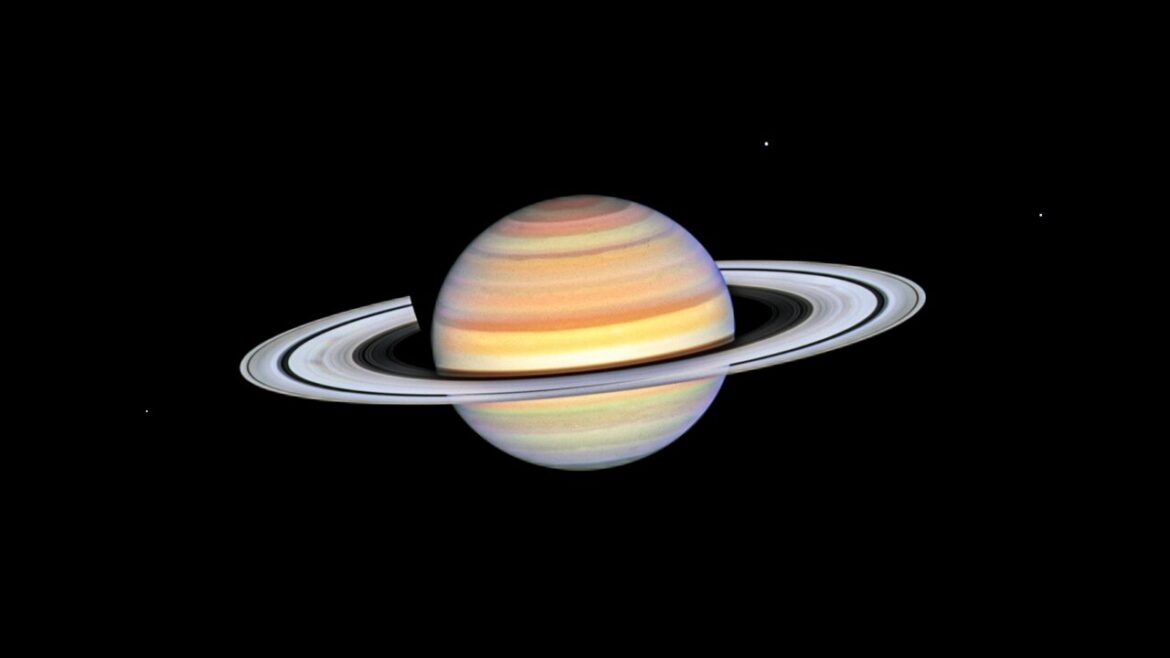

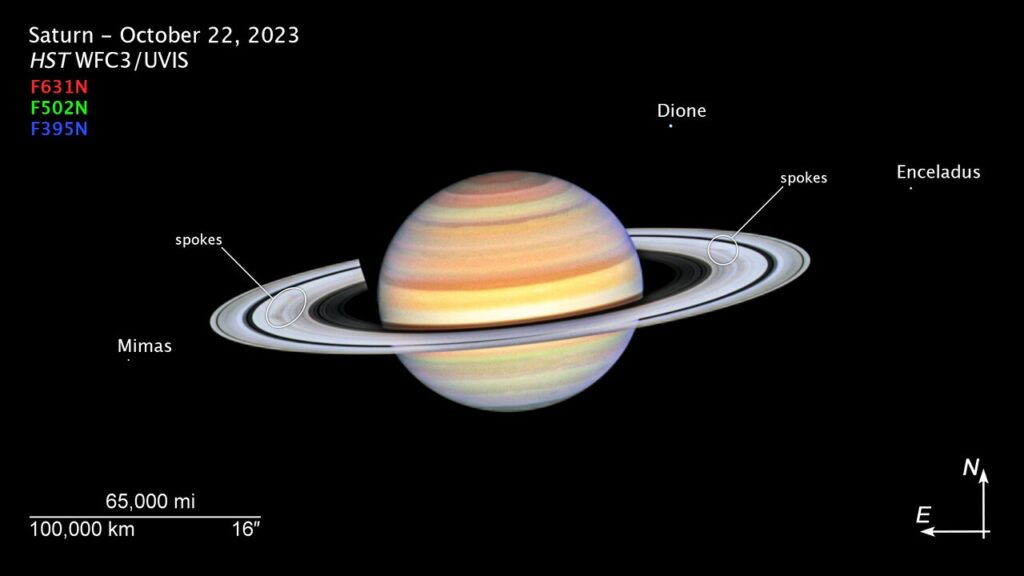

This photo of Saturn was taken by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope on 22 October 2023, when the ringed planet was approximately 1365 million kilometres from Earth. Hubble’s ultra-sharp vision reveals a phenomenon called ring spokes.

Saturn’s spokes are transient features that rotate along with the rings. Their ghostly appearance only persists for two or three rotations around Saturn. During active periods, freshly-formed spokes continuously add to the pattern.

In 1981, NASA’s Voyager 2 first photographed the ring spokes. Hubble continues observing Saturn annually as the spokes come and go. This cycle has been captured by Hubble’s Outer Planets Atmospheres Legacy (OPAL) program that began nearly a decade ago to annually monitor weather changes on all four gas-giant outer planets.

Hubble’s crisp images show that the frequency of spoke apparitions is seasonally driven, first appearing in OPAL data in 2021 but only on the morning (left) side of the rings. Long-term monitoring shows that both the number and contrast of the spokes vary with Saturn’s seasons. Saturn is tilted on its axis like Earth and has seasons lasting approximately seven years.

This year, these ephemeral structures appear on both sides of the planet simultaneously as they spin around the giant world. Although they look small compared with Saturn, their length and width can stretch longer than Earth’s diameter!

The OPAL team notes that the leading theory is that spokes are tied to interactions between Saturn’s powerful magnetic field and the sun. Planetary scientists think that electrostatic forces generated from this interaction levitate dust or ice above the ring to form the spokes, though after several decades no theory perfectly predicts the spokes. Continued Hubble observations may eventually help solve the mystery. This image was created with Hubble data from proposal 16995 (A. Simon).

Saturn’s spokes are transient features that rotate along with the rings. Their ghostly appearance only persists for two or three rotations around Saturn. During active periods, freshly-formed spokes continuously add to the pattern.

In 1981, NASA’s Voyager 2 first photographed the ring spokes. Hubble continues observing Saturn annually as the spokes come and go. This cycle has been captured by Hubble’s Outer Planets Atmospheres Legacy (OPAL) program that began nearly a decade ago to annually monitor weather changes on all four gas-giant outer planets.

Hubble’s crisp images show that the frequency of spoke apparitions is seasonally driven, first appearing in OPAL data in 2021 but only on the morning (left) side of the rings. Long-term monitoring shows that both the number and contrast of the spokes vary with Saturn’s seasons. Saturn is tilted on its axis like Earth and has seasons lasting approximately seven years.

This year, these ephemeral structures appear on both sides of the planet simultaneously as they spin around the giant world. Although they look small compared with Saturn, their length and width can stretch longer than Earth’s diameter!

The OPAL team notes that the leading theory is that spokes are tied to interactions between Saturn’s powerful magnetic field and the sun. Planetary scientists think that electrostatic forces generated from this interaction levitate dust or ice above the ring to form the spokes, though after several decades no theory perfectly predicts the spokes. Continued Hubble observations may eventually help solve the mystery.

Credit: NASA, ESA, STScI, A. Simon (NASA-GSFC)

Press release from ESA Hubble.