New dinosaur species from Utah lived at a time of major transition: Iani smithi provides insights into how dinosaurs weather mid-Cretaceous ecological change.

A new species of dinosaur from Utah sheds light on major North American ecological changes around 100 million years ago, according to a study published June 7, 2023 in the open-access journal PLoS ONE by Lindsay Zanno of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and colleagues.

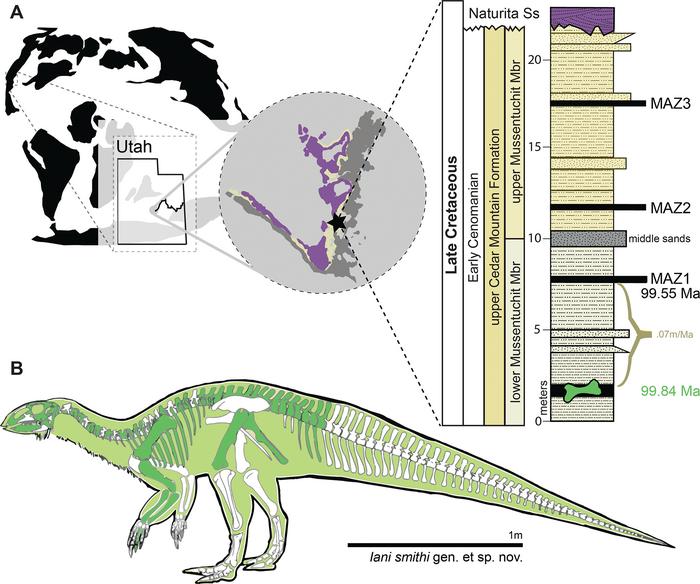

The boundary between the Early and Late Cretaceous Period saw major reassembly of global ecosystems associated with a peak in global temperatures. In the fossil record of western North America, this ecological shift has been well-documented for marine habitats, but less study has been done regarding terrestrial life. In this study, Zanno and colleagues identify a new dinosaur from the early Late Cretaceous Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah.

The new dinosaur, named Iani smithi, lived around 100 million years ago and is known from a single fossil specimen including a well-preserved skull and parts of the spine and limbs. The name derives from Ianus, a Roman deity who presided over transitions, referencing the changing world of the mid-Cretaceous.

Iani is a member of an early branch of the ornithopod dinosaurs, a group of mostly bipedal herbivores that also includes famous examples like Iguanodon and Tenontosaurus. Iani is the first early-diverging ornithopod known from the Late Cretaceous of North America.

This discovery, along with other recent reports from the same geologic formation, indicates that several major groups of dinosaurs survived into the early Late Cretaceous despite the ecological changes of the time, but exactly what these survivors were doing and how long they lasted is still unclear. Since Iani and its closest cousins are typically found in ancient coastal habitats along the shores of the now-vanished Western Interior Seaway, the authors suggest that more investigation into coastal deposits of similar age might yield further evidence to address these lingering questions.

The authors add: “Early ornithopods were once a common part of North American ecosystems, but we did not know they survived into the Late Cretaceous. The discovery of Iani helps us link their extinction on the continent with a major interval of global warming, one with striking similarities to our current climate crisis.”

Bibliographic information:

Zanno LE, Gates TA, Avrahami HM, Tucker RT, Makovicky PJ (2023) An early-diverging iguanodontian (Dinosauria: Rhabdodontomorpha) from the Late Cretaceous of North America, PLoS ONE 18(6): e0286042. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286042

Press release from the Public Library of Science.