Webb narrows atmospheric possibilities for Earth-sized exoplanet TRAPPIST-1 d

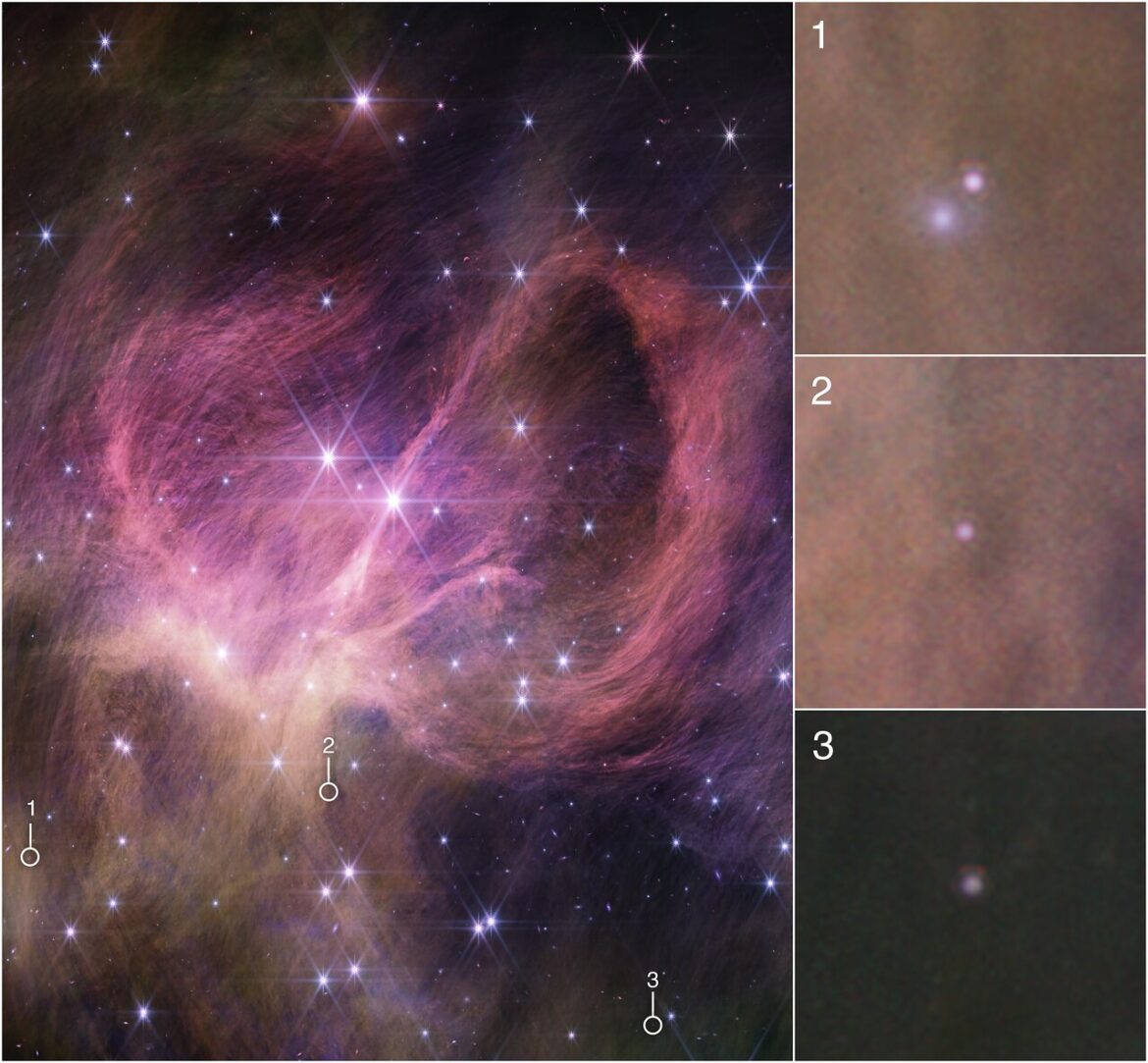

The exoplanet TRAPPIST-1 d intrigues astronomers looking for possibly habitable worlds beyond our solar system because it is similar in size to Earth, rocky, and resides in an area around its star where liquid water on its surface is theoretically possible. But according to a new study using data from the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope, it does not have an Earth-like atmosphere.

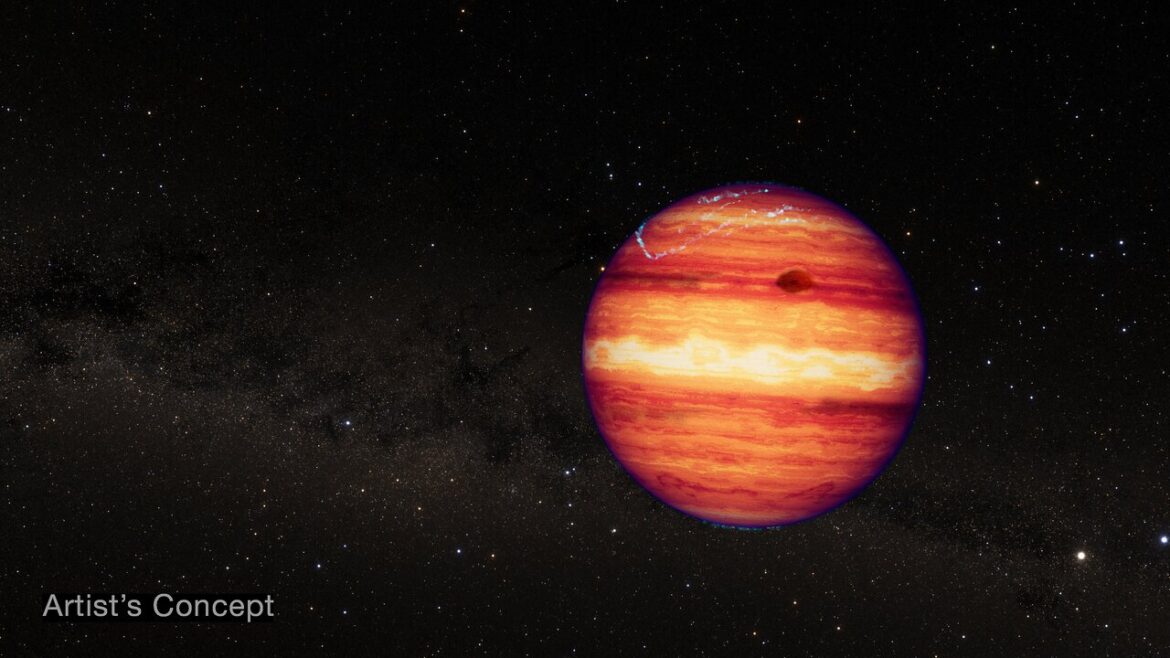

A protective atmosphere, a friendly Sun, and lots of liquid water — Earth is a special place. Using the unprecedented capabilities of the Webb, astronomers are on a mission to determine just how special, and rare, our home planet is. Can this temperate environment exist elsewhere, even around a different type of star? The TRAPPIST-1 system provides a tantalizing opportunity to explore this question, as it contains seven Earth-sized worlds orbiting the most common type of star in the galaxy: a red dwarf.

“Ultimately, we want to know if something like the environment we enjoy on Earth can exist elsewhere, and under what conditions. While the James Webb Space Telescope is giving us the ability to explore this question in Earth-sized planets for the first time, at this point we can rule out TRAPPIST-1 d from a list of potential Earth twins or cousins,”

said Caroline Piaulet-Ghorayeb of the University of Chicago and Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets (IREx) at Université de Montréal, lead author of the study published in The Astrophysical Journal.

Planet TRAPPIST-1 d

The TRAPPIST-1 system is located 40 light-years away and was revealed as the record-holder for most Earth-sized rocky planets around a single star in 2017, thanks to data from NASA’s retired Spitzer Space Telescope and other observatories. Due to that star being a dim, relatively cold red dwarf, the “habitable zone” – where the planet’s temperature may be just right, such that liquid surface water is possible – lies much closer to the star than in our solar system. TRAPPIST-1 d, the third planet from the red dwarf star, lies on the cusp of that temperate zone, yet its distance to its star is only 2 percent of Earth’s distance from the Sun. TRAPPIST-1 d completes an entire orbit around its star, its year, in only four Earth days.

Webb’s NIRSpec (Near-Infrared Spectrograph) instrument did not detect molecules from TRAPPIST-1 d that are common in Earth’s atmosphere, like water, methane, or carbon dioxide. However, Piaulet-Ghorayeb outlined several possibilities for the exoplanet that remain open for follow-up study.

“There are a few potential reasons why we don’t detect an atmosphere around TRAPPIST-1 d. It could have an extremely thin atmosphere that is difficult to detect, somewhat like Mars. Alternatively, it could have very thick, high-altitude clouds that are blocking our detection of specific atmospheric signatures — something more like Venus. Or, it could be a barren rock, with no atmosphere at all,” Piaulet-Ghorayeb said.

The star TRAPPIST-1

No matter what the case may be for TRAPPIST-1 d, it’s tough being a planet in orbit around a red dwarf star. TRAPPIST-1, the host star of the system, is known to be volatile, often releasing flares of high-energy radiation with the potential to strip off the atmospheres of its small planets, especially those orbiting most closely. Nevertheless, scientists are motivated to seek signs of atmospheres on the TRAPPIST-1 planets because red dwarf stars are the most common stars in our galaxy. If planets can hold on to an atmosphere here, under waves of harsh stellar radiation, they could, as the saying goes, make it anywhere.

“Webb’s sensitive infrared instruments are allowing us to delve into the atmospheres of these smaller, colder planets for the first time,” said Björn Benneke of IREx at Université de Montréal, a co-author of the study. “We’re really just getting started using Webb to look for atmospheres on Earth-sized planets, and to define the line between planets that can hold onto an atmosphere, and those that cannot.”

The outer TRAPPIST-1 planets

Webb observations of the outer TRAPPIST-1 planets are ongoing, which hold both potential and peril. On the one hand, Benneke said, planets e, f, g, and h may have better chances of having atmospheres because they are further away from the energetic eruptions of their host star. However, their distance and colder environment will make atmospheric signatures more difficult to detect, even with Webb’s infrared instruments.

“All hope is not lost for atmospheres around the TRAPPIST-1 planets,” Piaulet-Ghorayeb said. “While we didn’t find a big, bold atmospheric signature at planet d, there is still potential for the outer planets to be holding onto a lot of water and other atmospheric components.”

“Our detective work is just beginning. While TRAPPIST-1 d may prove a barren rock illuminated by a cruel red star, the outer planets TRAPPIST-1e, f, g, and h, may yet possess thick atmospheres,” added Ryan MacDonald, a co-author of the paper, now at the University of St Andrews in the United Kingdom, and previously at the University of Michigan. “Thanks to Webb we now know that TRAPPIST-1 d is a far cry from a hospitable world. We’re learning that the Earth is even more special in the cosmos.”

The TRAPPIST-1 system is intriguing to scientists for a few reasons. Not only does the system have seven Earth-sized rocky worlds, but its star is a red dwarf, the most common type of star in the Milky Way galaxy. If an Earth-sized world can maintain an atmosphere here, and thus have the potential for liquid surface water, the chance of finding similar worlds throughout the galaxy is much higher. In studying the TRAPPIST-1 planets, scientists are determining the best methods for separating starlight from potential atmospheric signatures in data from the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope. The star TRAPPIST-1’s variability, with frequent flares, provides a challenging testing ground for these methods.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, J. Olmsted (STScI)

Bibliographic information:

Caroline Piaulet-Ghorayeb et al., ApJ 989 181 2025, DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/adf207

Press release from ESA Webb.