Hubble finds strong evidence for intermediate-mass black hole in Omega Centauri

An international team of astronomers has used more than 500 images from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope spanning two decades to detect seven fast-moving stars in the innermost region of Omega Centauri, the largest and brightest globular cluster in the sky. These stars provide compelling new evidence for the presence of an intermediate-mass black hole.

Intermediate-mass black holes (IMBHs) are a long-sought ‘missing link’ in black hole evolution. Only a few other IMBH candidates have been found to date. Most known black holes are either extremely massive, like the supermassive black holes that lie at the cores of large galaxies, or relatively lightweight, with a mass less than 100 times that of the Sun. Black holes are one of the most extreme environments humans are aware of, and so they are a testing ground for the laws of physics and our understanding of how the Universe works. If IMBHs exist, how common are they? Does a supermassive black hole grow from an IMBH? How do IMBHs themselves form? Are dense star clusters their favoured home?

Omega Centauri is visible from Earth with the naked eye and is one of the favourite celestial objects for stargazers in the southern hemisphere. Although the cluster is 17 700 light-years away, lying just above the plane of the Milky Way, it appears almost as large as the full Moon when seen from a dark rural area. The exact classification of Omega Centauri has evolved through time, as our ability to study it has improved. It was first listed in Ptolemy’s catalogue nearly two thousand years ago as a single star. Edmond Halley reported it as a nebula in 1677, and in the 1830s the English astronomer John Herschel was the first to recognise it as a globular cluster.

Globular clusters typically consist of up to one million old stars tightly bound together by gravity and are found both in the outskirts and central regions of many galaxies, including our own. Omega Centauri has several characteristics that distinguish it from other globular clusters: it rotates faster than a run-of-the-mill globular cluster, and its shape is highly flattened. Moreover, Omega Centauri is about 10 times as massive as other big globular clusters, almost as massive as a small galaxy.

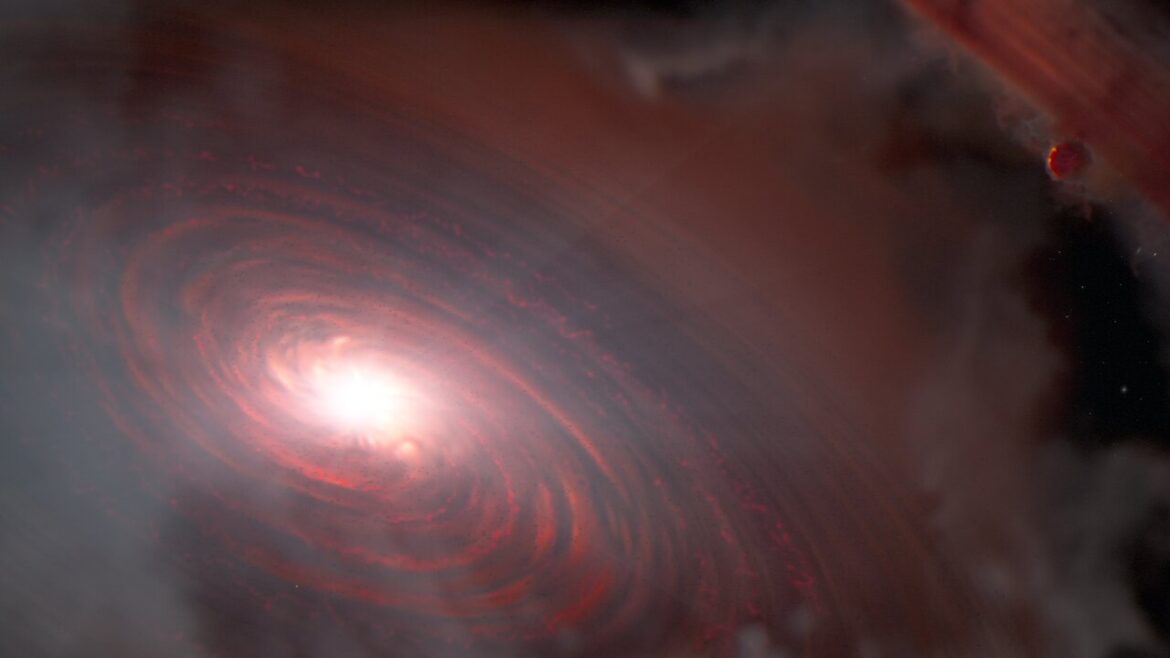

Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, M. Häberle (MPIA)

Omega Centauri consists of roughly 10 million stars that are gravitationally bound. An international team has now created an enormous catalogue of the motions of these stars, measuring the velocities for 1.4 million stars by studying over 500 Hubble images of the cluster. Most of these observations were intended to calibrate Hubble’s instruments rather than for scientific use, but they turned out to be an ideal database for the team’s research efforts. The extensive catalogue, which is the largest catalogue of motions for any star cluster to date, will be made openly available (more information is available here).

“We discovered seven stars that should not be there,” explained Maximilian Häberle of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany, who led this investigation. “They are moving so fast that they should escape the cluster and never come back. The most likely explanation is that a very massive object is gravitationally pulling on these stars and keeping them close to the centre. The only object that can be so massive is a black hole, with a mass at least 8200 times that of our Sun.”

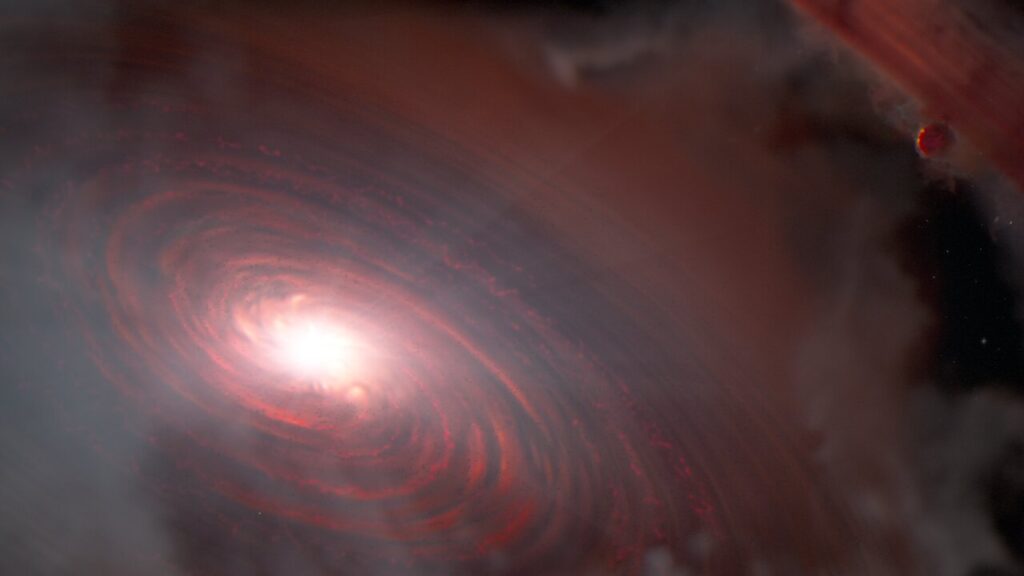

Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, M. Häberle (MPIA)

Several studies have suggested the presence of an IMBH in Omega Centauri [1]. However, other studies proposed that the mass could be contributed by a central cluster of stellar-mass black holes, and had suggested the lack of fast-moving stars above the necessary escape velocity made an IMBH less likely in comparison.

“This discovery is the most direct evidence so far of an IMBH in Omega Centauri,” added team lead Nadine Neumayer, also of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, who initiated the study with Anil Seth of the University of Utah in the United States. “This is exciting because there are only very few other black holes known with a similar mass. The black hole in Omega Centauri may be the best example of an IMBH in our cosmic neighbourhood.”

If confirmed, at its distance of 17 700 light-years the candidate black hole resides closer to Earth than the 4.3 million solar mass black hole in the centre of the Milky Way, which is 26 000 light-years away. Besides the Galactic centre, it would also be the only known case of a number of stars closely bound to a massive black hole.

The science team now hopes to characterise the black hole. While it is believed to measure at least 8200 solar masses, its exact mass and its precise position are not fully known. The team also intends to study the orbits of the fast-moving stars, which requires additional measurements of the respective line-of-sight velocities. The team has been granted time with the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope to do just that, and also has other pending proposals to use other observatories.

Omega Centauri was also a recent feature of a new data release from ESA’s Gaia mission, which contained over 500 000 stars.

“Even after 30 years, the Hubble Space Telescope with its imaging instruments is still one of the best tools for high-precision astrometry in crowded stellar fields, regions where Hubble can provide added sensitivity from ESA’s Gaia mission observations,” shared team member Mattia Libralato of the National Institute for Astrophysics in Italy (INAF), and previously of AURA for the European Space Agency during the time of this study. “Our results showcase Hubble’s high resolution and sensitivity that are giving us exciting new scientific insights and will give a new boost to the topic of IMBHs in globular clusters.”

The results have been published online today in the journal Nature.

This image shows the central region of the Omega Centauri globular cluster, where the IMBH candidate was found.

Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, M. Häberle (MPIA)

Notes

[1] In 2008, the Hubble Space Telescope and the Gemini Observatory found that the explanation behind Omega Centauri’s peculiarities may be a black hole hidden in its centre.

Press release from ESA Hubble.