Hubble and a new study published in Nature Astronomy cast doubt on the certainty of a collision between the Milky Way and the Andromeda galaxy

Over a decade’s worth of NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope data was used to re-examine the long-held prediction that the Milky Way galaxy will collide with the Andromeda galaxy in about 4.5 billion years. The astronomers found that, based on the latest observational data from Hubble as well as the Gaia space telescope, there is only a 50-50 chance of the two galaxies colliding within the next 10 billion years. The study also found that the presence of the Large Magellanic Cloud can affect the trajectory of the Milky Way and make the collision less likely. The researchers emphasize that predicting the long-term future of galaxy interactions is highly uncertain, but the new findings challenge the previous consensus and suggest the fate of the Milky Way remains an open question.

Credit: NASA, ESA, STScI, Till Sawala (University of Helsinki), DSS, J. DePasquale (STScI)

As far back as 1912, astronomers realized that the Andromeda galaxy — then thought to be only a nebula — was headed our way. A century later, astronomers using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope were able to measure the sideways motion of Andromeda and found it was so negligible that an eventual head-on collision with the Milky Way seemed almost certain.

A smashup between our own galaxy and Andromeda would trigger a firestorm of star birth, supernovae, and maybe toss our Sun into a different orbit. Simulations had suggested it was inevitable.

However, a new study using data from Hubble and ESA’s Gaia suggests this may not necessarily be the case. Researchers combining observations from the two space observatories re-examined the long-held prediction of a Milky Way – Andromeda collision, and found it is far less inevitable than astronomers had previously suspected.

“We have the most comprehensive study of this problem today that actually folds in all the observational uncertainties,” said Till Sawala, astronomer at the University of Helsinki in Finland and lead author of the study, which appears today in the journal Nature Astronomy.

His team includes researchers at Durham University, United Kingdom; the University of Toulouse, France; and the University of Western Australia. They found that there is approximately a 50-50 chance of the two galaxies colliding within the next 10 billion years. They based this conclusion on computer simulations using the latest observational data.

Sawala emphasized that predicting the long-term future of galaxy interactions is highly uncertain, but the new findings challenge the previous consensus and suggest the fate of the Milky Way remains an open question.

“Even using the latest and most precise observational data available, the future of the Local Group of several dozen galaxies is uncertain. Intriguingly, we find an almost equal probability for the widely publicized merger scenario, or, conversely, an alternative one where the Milky Way and Andromeda survive unscathed,” said Sawala.

The collision of the two galaxies had seemed much more likely in 2012, when astronomers Roeland van der Marel and Tony Sohn of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland published a detailed analysis of Hubble observations over a five-to-seven-year period, indicating a direct impact in no more than 5 billion years.

“It’s somewhat ironic that, despite the addition of more precise Hubble data taken in recent years, we are now less certain about the outcome of a potential collision. That’s because of the more complex analysis and because we consider a more complete system. But the only way to get to a new prediction about the eventual fate of the Milky Way will be with even better data,” said Sawala.

Astronomers considered 22 different variables that could affect the potential collision between our galaxy and our neighbor, and ran 100,000 simulations called Monte Carlo simulations stretching to 10 billion years into the future.

“Because there are so many variables that each have their errors, that accumulates to rather large uncertainty about the outcome, leading to the conclusion that the chance of a direct collision is only 50% within the next 10 billion years,” said Sawala.

“The Milky Way and Andromeda alone would remain in the same plane as they orbit each other, but this doesn’t mean they need to crash. They could still go past each other,” said Sawala.

Researchers also considered the effects of the orbits of Andromeda’s large satellite galaxy, M33, and a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way called the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC).

“The extra mass of Andromeda’s satellite galaxy M33 pulls the Milky Way a little bit more towards it. However, we also show that the LMC pulls the Milky Way off the orbital plane and away from Andromeda. It doesn’t mean that the LMC will save us from that merger, but it makes it a bit less likely,” said Sawala.

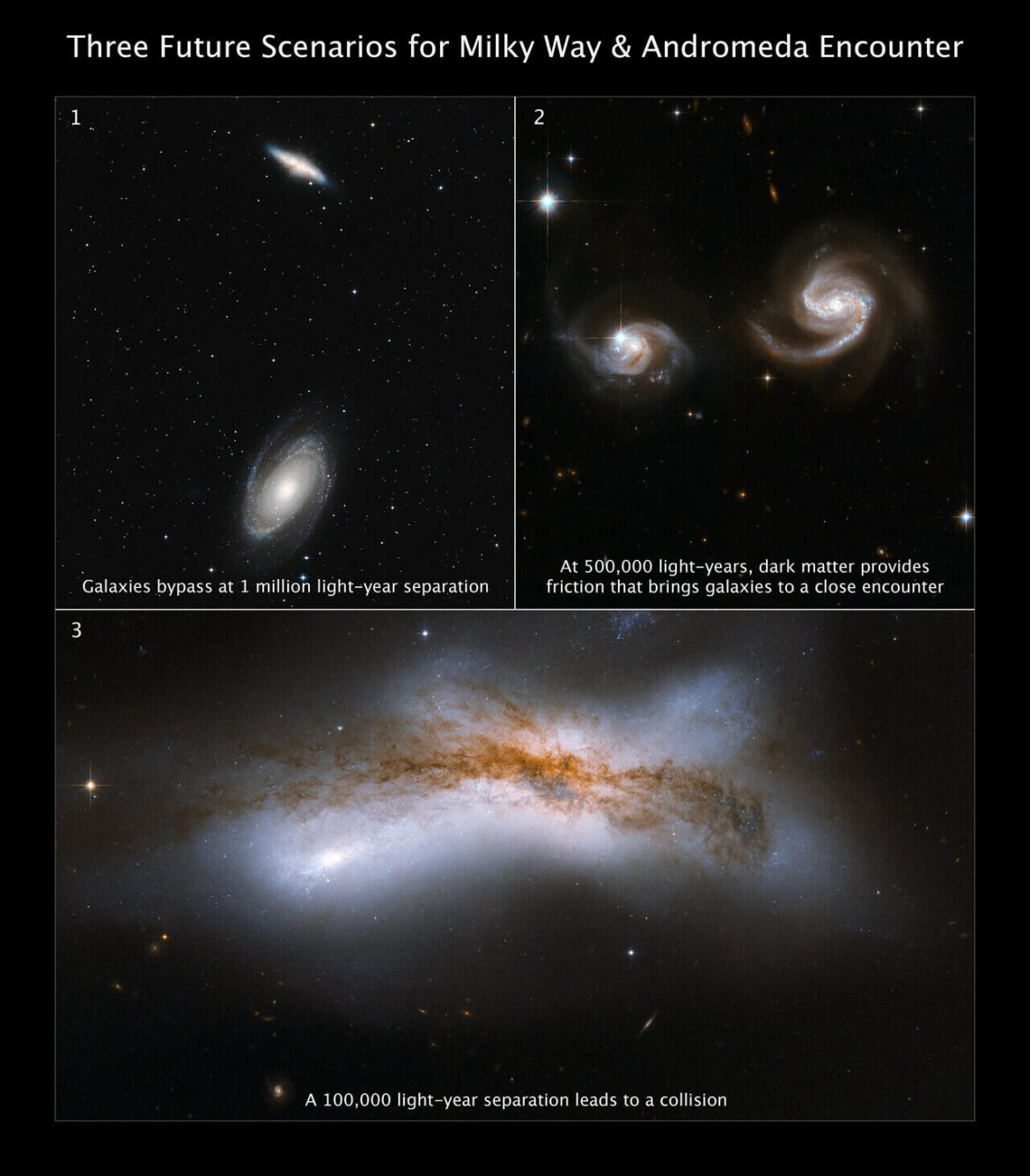

In about half of the simulations, the two main galaxies fly past each other separated by around half a million light-years or less (five times the Milky Way’s diameter). They move outward but then come back and eventually merge in the far future. The gradual decay of the orbit is caused by a process called dynamical friction between the vast dark-matter halos that surround each galaxy at the beginning.

In most of the other cases, the galaxies don’t even come close enough for dynamical friction to work effectively. In this case, the two galaxies can continue their orbital waltz for a very long time.

The new result also still leaves a small chance of around 2% for a head-on collision between the galaxies in only 4 to 5 billion years. Considering that the warming Sun makes Earth uninhabitable in roughly 1 billion years, and the Sun itself will likely burn out in 5 billion years, a collision with Andromeda is the least of our cosmic worries.

Bibliographic information:

Sawala, T., Delhomelle, J., Deason, A.J. et al, No certainty of a Milky Way–Andromeda collision. Nat Astron (2025), DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02563-1

Press release from ESA Hubble.