Black Death shaped evolution of immunity genes, setting course for how we respond to disease today

An international team of scientists who analyzed centuries-old DNA from victims and survivors of the Black Death pandemic has identified key genetic differences that determined who lived and who died, and how those aspects of our immune systems have continued to evolve since that time.

Researchers from McMaster University, the University of Chicago, the Pasteur Institute and other organizations analyzed and identified genes that protected some against the devastating bubonic plague pandemic that swept through Europe, Asia and Africa nearly 700 years ago. Their study has been published in the journal Nature.

The same genes that once conferred protection against the Black Death are today associated with an increased susceptibility to autoimmune diseases such as Crohn’s and rheumatoid arthritis, the researchers report.

The team focused on a 100-year window before, during and after the Black Death, which reached London in the mid-1300s. It remains the single greatest human mortality event in recorded history, killing upwards of 50 per cent of the people in what were then some of the most densely populated parts of the world.

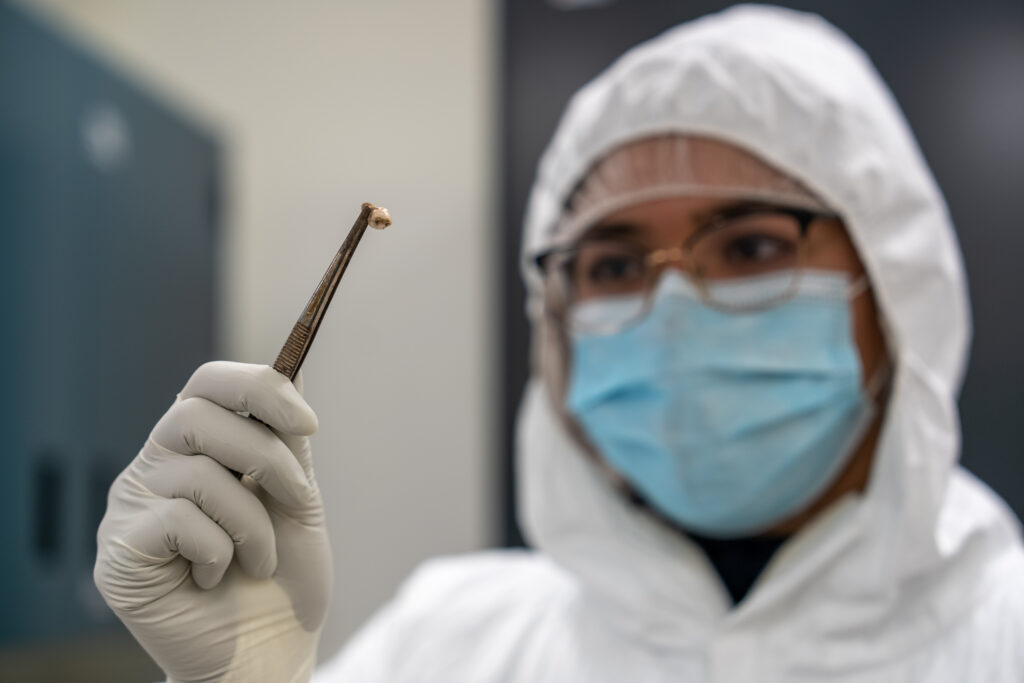

More than 500 ancient DNA samples were extracted and screened from the remains of individuals who had died before the plague, died from it or survived the Black Death in London, including individuals buried in the East Smithfield plague pits used for mass burials in 1348-9. Additional samples were taken from remains buried in five other locations across Denmark.

Scientists searched for signs of genetic adaptation related to the plague, which is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis.

They identified four genes that were under selection, all of which are involved in the production of proteins that defend our systems from invading pathogens and found that versions of those genes, called alleles, either protected or rendered one susceptible to plague.

Individuals with two identical copies of a particular gene, known as ERAP2, survived the pandemic at a much higher rates than those with the opposing set of copies, because the ‘good’ copies allowed for more efficient neutralization of Y. pestis by immune cells.

“When a pandemic of this nature – killing 30 to 50 per cent of the population – occurs, there is bound to be selection for protective alleles in humans, which is to say people susceptible to the circulating pathogen will succumb. Even a slight advantage means the difference between surviving or passing. Of course, those survivors who are of breeding age will pass on their genes,” explains evolutionary geneticist Hendrik Poinar, an author of the Nature paper, director of McMaster’s Ancient DNA Centre, and a principal investigator with the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research and McMaster’s Global Nexus for Pandemics & Biological Threats.

Europeans living at the time of the Black Death were initially very vulnerable because they had had no recent exposure to Yersinia pestis. As waves of the pandemic occurred again and again over the following centuries, mortality rates decreased.

Researchers estimate that people with the ERAP2 protective allele (the good copy of the gene, or trait), were 40 to 50 per cent more likely to survive than those who did not.

“The selective advantage associated with the selected loci are among the strongest ever reported in humans showing how a single pathogen can have such a strong impact to the evolution of the immune system,” says human geneticist Luis Barreiro, an author on the paper, and professor in Genetic Medicine at the University of Chicago.

The team reports that over time our immune systems have evolved to respond in different ways to pathogens, to the point that what had once been a protective gene against plague in the Middle Ages is today associated with increased susceptibility to autoimmune diseases. This is the balancing act upon which evolution plays with our genome.

“This highly original work has been possible only through a successful collaboration between very complementary teams working on ancient DNA, on human population genetics and the interaction between live virulent Yersinia pestis and immune cells,” says Javier Pizarro-Cerda, head of the Yersinia Research Unit and director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Plague at the Pasteur Institute.

“Understanding the dynamics that have shaped the human immune system is key to understanding how past pandemics, like the plague, contribute to our susceptibility to disease in modern times,” says Poinar.

The findings, the result of seven years of work from graduate student Jennifer Klunk, formally of McMaster’s Ancient DNA Centre and postdoctoral fellow Tauras Vigylas, from the University of Chicago, allowed for an unprecedented look at the immune genes of victims of the Black Death.

The research was funded in part by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), The National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, under the Humans and the Microbiome program.

Press release from McMaster University, by Michelle Donovan on how the Black Death shaped the evolution of immunity genes, setting course for how we respond to disease today.