Hubble observes a changing exoplanet atmosphere at WASP-121 b

An international team of astronomers assembled and reprocessed Hubble observations of the exoplanet made in the years 2016, 2018 and 2019. This provided them with a unique dataset that allowed them not only to analyse the atmosphere of WASP 121-b, but also to compare the state of the exoplanet’s atmosphere across several years. They found clear evidence that the observations of WASP-121 b were varying in time. The team then used sophisticated modelling techniques to demonstrate that these temporal variations could be explained by weather patterns in the exoplanet’s atmosphere.

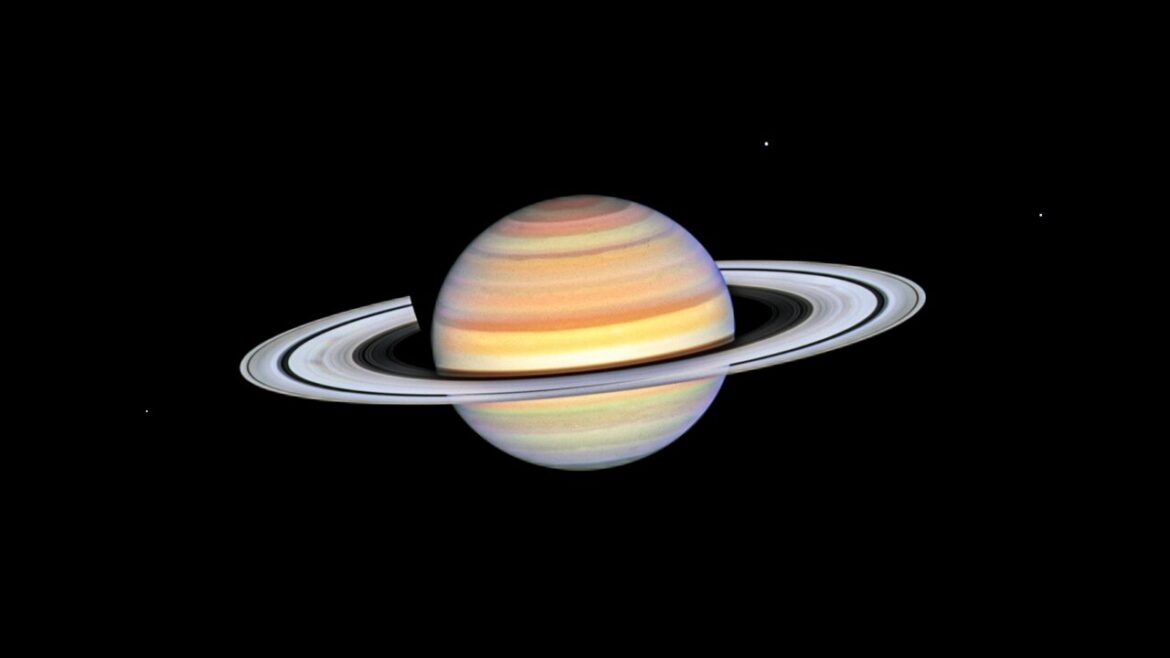

Credit: NASA, ESA, Q. Changeat et al., M. Zamani (ESA/Hubble)

An international team of astronomers has assembled and reprocessed observations of the exoplanet WASP-121 b that were collected with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope in the years 2016, 2018 and 2019. This provided them with a unique dataset that allowed them not only to analyse the atmosphere of WASP 121 b, but also to compare the state of the exoplanet’s atmosphere across several years. They found clear evidence that the observations of WASP-121 b were varying in time. The team then used sophisticated modelling techniques to demonstrate that these temporal variations could be explained by weather patterns in the exoplanet’s atmosphere.

Observing exoplanets — planets beyond our Solar System — is challenging, because of both their distance from Earth and the fact that they mostly orbit stars that are far bigger and brighter than the planets are. This means that astronomers who have been able to observe an exoplanet with a telescope as sophisticated as Hubble typically have to combine all their data in order to get enough information to make confident deductions about the exoplanet’s properties. By combining the observations to increase the strength of the exoplanet signal, astronomers can construct an averaged picture of its atmosphere, but this does not tell them whether it is changing. In other words, they cannot study the weather on other worlds using this averaging method. Studying weather requires far more data of high quality, taken over a wider period of time. Fortunately, Hubble has now been active for such an impressive length of time that a vast archive of Hubble data exists, sometimes with multiple sets of observations of the same celestial object — and that includes the exoplanet WASP-121 b.

WASP-121 b (also known as Tylos) is a well-studied hot Jupiter [1] that orbits a star that lies about 880 light-years from Earth, completing a full orbit in a very brisk 30-hour period. Its extremely close proximity to its host star means that it is tidally locked [2], and that the star-facing hemisphere is very hot, with temperatures exceeding 3000 Kelvins [3]. The team combined four sets of archival observations of WASP-121 b, all made using Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC 3). The complete assembled dataset included observations of: WASP-121 b transiting in front of its star (taken in June 2016); WASP-121 b transiting behind its star, also known as a secondary eclipse (taken in November 2016); and two phase-curves [4] of WASP-121 b (taken in March 2018 and February 2019 respectively). The team took the unique step of processing each dataset in the same way, even if it had been previously processed by a different team. Exoplanet data processing is time consuming and complicated, but nonetheless it was worth it because it allowed the team to directly compare the processed data from each set of observations with one another. One of the principal investigators of the team, Quentin Changeat, an ESA Research Fellow at the Space Telescope Science Institute, elaborates:

“Our dataset represents a significant amount of observing time for a single planet and is currently the only consistent set of such repeated observations. The information that we extracted from those observations was used to characterise (infer the chemistry, temperature, and clouds) of the atmosphere of WASP-121 b at different times. This provided us with an exquisite picture of the planet, changing in time.”

After cleaning each dataset, the team found clear evidence that the observations of WASP-121 b were varying in time. While instrumental effects could remain, the data showed an apparent shift in the exoplanet’s hot spot [5] and differences in spectral signature (which signifies the chemical composition of the exoplanet’s atmosphere) indicative of a changing atmosphere. Next, the team used highly sophisticated computational models to attempt to understand observed behaviour of the exoplanet’s atmosphere. The models indicated that their results could be explained by quasi-periodic weather patterns, specifically massive cyclones that are repeatedly created and destroyed as a result of the huge temperature difference between the star-facing and dark side of the exoplanet. This result represents a significant step forward in potentially observing weather patterns on exoplanets.

“The high resolution of our exoplanet atmosphere simulations allows us to accurately model the weather on ultra-hot planets like WASP-121 b,” explained Jack Skinner, a postdoctoral fellow at the California Institute of Technology and co-leader of this study. “Here we make a significant step forward by combining observational constraints with atmosphere simulations to understand the time-varying weather on these planets.”

“Weather on Earth is responsible for many aspects of our life, and in fact the long-term stability of Earth’s climate and its weather is likely the reason why life could emerge in the first place,” added Changeat. “Studying exoplanets’ weather is vital to understanding the complexity of exoplanet atmospheres, especially in our search for exoplanets with habitable conditions.”

Future observations with Hubble and other powerful telescopes, including Webb, will provide greater insight into weather patterns on distant worlds: and ultimately, possibly to finding exoplanets with stable long-term climates and weather patterns.

Notes

[1] Hot Jupiters are a type of exoplanet with no direct Solar System analogue: they are inflated gas giants that orbit very close to their parent stars, often performing a complete orbit in a matter of a few days.

[2] Tidal locking refers to the situation where an orbiting body always presents the same hemisphere to the object that it orbits. For example, the Moon is tidally locked to Earth, which explains why the surface of the Moon always looks the same from our perspective here on Earth. In some cases, the two bodies might be tidally locked to one another, although this is not the case for the Moon and Earth: from the perspective of an astronaut on the Moon, Earth still appears to rotate on its own axis. Tidally locked planets will have an extremely uneven temperature distribution across their entire surface, with the star-facing hemisphere much hotter than the other.

[3] Kelvins (K) are the unit of temperature typically used by many scientists, including astronomers. Kelvins are the same in size as degrees Celsius (℃), however, the Kelvin scale is offset from the Celsius scale, which is set to zero at the freezing point of water at one atmosphere of pressure. In contrast, zero on the Kelvin scale is known as absolute zero, and is thought to be the lowest temperature possible, where all kinetic activity of all molecules ceases. 0 K is equivalent to –273.15 ℃.

[4] Exoplanet phase curves show the varying amount of light received from a star-exoplanet system as the exoplanet orbits its parent star.

[5] Exoplanet hot spots are, as the name suggests, the hottest spots on the exoplanet’s surface. Whilst it would be intuitive to suppose that the hotspot will always be at the point on the planet closest to the star, in fact many studies have shown that exoplanet hotspots are frequently offset. This may be due to wind or other atmospheric patterns on the exoplanets themselves.

Link to the Science paper

Press release from ESA Hubble.

![Hubble measures the size of LTT 1445Ac, the nearest transiting Earth-sized planet [Image description: This is an artist’s concept of nearby exoplanet LTT 1445Ac, which appears as a large whitish-orange disk at lower left. The rocky planet orbits a red dwarf star which is a bright red sphere in the image centre. The star is in a triple system, with two closely orbiting red dwarfs – a pair of red dots – seen at upper right.]](https://scientificult.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/heic2311a-1170x658.jpg)

![[Image description: This is an artist’s concept of nearby exoplanet LTT 1445Ac, which appears as a large whitish-orange disk at lower left. The rocky planet orbits a red dwarf star which is a bright red sphere in the image centre. The star is in a triple system, with two closely orbiting red dwarfs – a pair of red dots – seen at upper right.]](https://scientificult.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/heic2311a-1024x576.jpg)

![[Image description: A red giant star is in the centre of the image. An exoplanet passing in front of the star (called a transit) is shown in silhouette in a number of steps from left to right. A similar linear trajectory is shown at the bottom of the image. It is called a grazing transit rather than a full transit because it just clips the bottom of the star. This is considered a less accurate observing geometry in estimating the planet’s size. Hubble’s accuracy can distinguish between these two scenarios, yielding a precise measurement of the planet’s diameter.]](https://scientificult.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/heic2311b-1024x576.jpg)