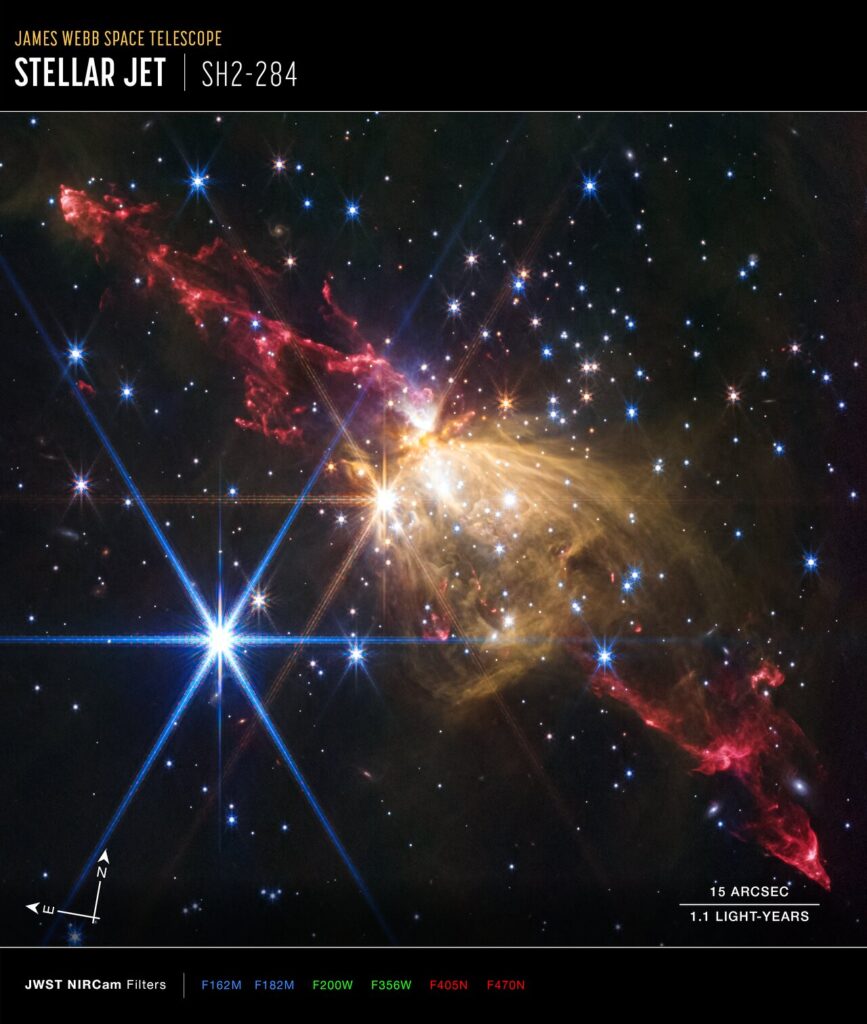

Webb observes Sharpless 2-284, a Herbig-Haro object, an immense stellar jet on outskirts of our Milky Way

Way out toward the edge of our Milky Way galaxy, a young star that is still forming is sending out a birth announcement to the Universe in the form of a celebratory looking firework. These seething twin jets of hot gasses are blazing across 8 light-years – twice the distance between our Sun and the nearest star system. Superheated gases falling onto the massive star are blasted back into space along the star’s rotational axis and powerful magnetic fields confine the jets to narrow beams. The NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope witnessed the spectacle in infrared light. The jets are plowing into interstellar dust and gas, creating fascinating details captured only by Webb.

Its detection provides evidence that HH jets scale with the mass of their parent stars—the more massive the stellar engine driving the plasma, the larger the resulting jet.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Y. Cheng (NAOJ), J. DePasquale (STScI)

A blowtorch of seething gasses erupting from a volcanically growing monster star has been captured by Webb. Stretching across 8 light-years, the length of the stellar eruption is approximately twice the distance between our Sun and the nearby Alpha Centauri system. The size and strength of this particular stellar jet, known as Sharpless 2-284 (Sh2-284 for short), qualifies it as rare, say researchers.

The outflow is streaking across space at hundreds of thousands of kilometres per hour. The central protostar, weighing as much as ten of our Suns, is located 15,000 light-years away in the outer reaches of our galaxy.

The Webb discovery was serendipitous. “We didn’t really know there was a massive star with this kind of super-jet out there before the observation. Such a spectacular outflow of molecular hydrogen from a massive star is rare in other regions of our galaxy,” said lead author Yu Cheng of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan.

This unique class of stellar fireworks, called Herbig-Haro (HH) objects, are highly collimated jets of plasma shooting out from newly forming stars. Such jetted outflows are a star’s spectacular “birth announcement” to the Universe. Some of the infalling gas building up around the central star is blasted along the star’s spin axis, likely under the influence of magnetic fields.

Today, well over 300 HH objects have been observed, but mainly from low-mass stars. These spindle-like jets offer clues into the nature of newly forming stars. The energetics, narrowness, and evolutionary time scales of HH objects all serve to constrain models of the environment and physical properties of the young stellar object powering the outflow.

“I was really surprised at the order, symmetry, and size of the jet when we first looked at it,” said co-author Jonathan Tan of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville and Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Its detection offers evidence that HH jets must scale up with the mass of the star powering them. The more massive the stellar engine propelling the plasma, the larger the gusher’s size.

The jet’s detailed filamentary structure, captured by Webb’s crisp resolution in infrared light, is evidence the jet is plowing into interstellar dust and gas. This creates separate knots, bow shocks, and linear chains.

The tips of the jet, lying in opposite directions, encapsulate the history of the star’s formation. “Originally the material was close into the star, but over 100,000 years the tips were propagating out, and then the stuff behind is a younger outflow,” said Tan.

Outlier

At nearly twice the distance from the galactic center as our Sun, the host proto-cluster that’s home to the voracious jet is on the periphery of our Milky Way galaxy.

Within the cluster, a few hundred stars are still forming. Being in the galactic hinterlands means the stars are deficient in heavier elements beyond hydrogen and helium. This is measured as metallicity, which gradually increases over cosmic time as each passing stellar generation expels end products of nuclear fusion through winds and supernovae. The low metallicity of Sh2-284 is a reflection of its relatively pristine nature, making it a local analog for the environments in the early universe that were also deficient in heavier elements.

“Webb’s exquisite data have also shown us that relatively more stars seem to form at lower masses in Sh2-284 than in closer, more metal-rich clusters,” said co-author Morten Andersen, of the European Southern Observatory, and lead author of a second paper on the Webb data. “This cluster is an excellent region to help us understand star formation throughout the Universe.”

“Massive stars, like the one found inside this cluster, have very important influences on the evolution of galaxies. Our discovery is shedding light on the formation mechanism of massive stars in low metallicity environments, so we can use this massive star as a laboratory to study what was going on in earlier cosmic history,” added Cheng.

Unrolling stellar tapestry

Stellar jets, which are powered by the gravitational energy released as a star grows in mass, encode the formation history of the protostar.

“Webb’s new images are telling us that the formation of massive stars in such environments could proceed via a relatively stable disc around the star that is expected in theoretical models of star formation known as core accretion,” said Tan. “Once we found a massive star launching these jets, we realised we could use the Webb observations to test theories of massive star formation. We developed new theoretical core accretion models that were fit to the data, to basically tell us what kind of star is in the center. These models imply that the star is about 10 times the mass of the Sun and is still growing and has been powering this outflow.”

For more than 30 years, astronomers have disagreed about how massive stars form. Some think a massive star requires a very chaotic process, called competitive accretion.

In the competitive accretion model, material falls in from many different directions so that the orientation of the disc changes over time. The outflow is launched perpendicularly, above and below the disc, and so would also appear to twist and turn in different directions.

“However, what we’ve seen here, because we’ve got the whole history – a tapestry of the story – is that the opposite sides of the jets are nearly 180 degrees apart from each other. That tells us that this central disc is held steady and validates a prediction of the core accretion theory,” said Tan.

Where there’s one massive star, there could be others in this outer frontier of the Milky Way. Other massive stars may not yet have reached the point of firing off Roman-candle-style outflows. Data from the Atacama Large Millimeter Array in Chile, also presented in this study, has found another dense stellar core that could be in an earlier stage of construction.

The paper has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

The north and east compass arrows show the orientation of the image on the sky. Note that the relationship between north and east on the sky (as seen from below) is flipped to the direction arrows on a map of the ground (as seen from above).

The scale bar is labeled in light-years, which is the distance that light travels in one Earth-year, and arcsec (It takes 1.1 years for light to travel a distance equal to the length of the scale bar.) One light-year is equal to about 5.88 trillion miles or 9.46 trillion kilometers.

This image shows invisible near-infrared wavelengths of light that have been translated into visible-light colors. The color key shows which NIRCam filters were used when collecting the light. The color of each filter name is the visible light color used to represent the infrared light that passes through that filter.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Y. Cheng (NAOJ), J. DePasquale (STScI)

Press release from ESA Webb.