Webb Reveals an Exoplanet Atmosphere as Never Seen Before

The NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope just scored another first: a molecular and chemical profile of a distant world’s skies.

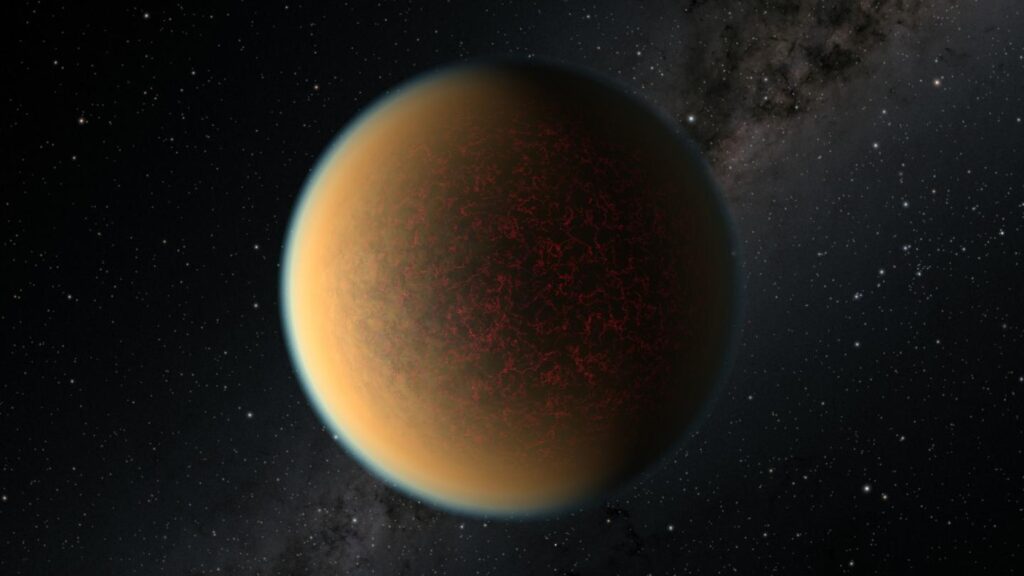

The NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope just scored another first: a molecular and chemical portrait of a distant world’s skies. While Webb and other space telescopes, including the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, have previously revealed isolated ingredients of this heated planet’s atmosphere, the new readings provide a full menu of atoms, molecules, and even signs of active chemistry and clouds. The latest data also give a hint of how these clouds might look up close: broken up rather than as a single, uniform blanket over the planet.

The telescope’s array of highly sensitive instruments was trained on the atmosphere of WASP-39 b, a “hot Saturn” (a planet about as massive as Saturn but in an orbit tighter than Mercury) orbiting a star some 700 light-years away. This Saturn-sized exoplanet was one of the first examined by the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope when it began regular science operations. The results have excited the exoplanet science community. Webb’s exquisitely sensitive instruments have provided a profile of WASP-39 b’s atmospheric constituents and identified a plethora of contents, including water, sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide, sodium and potassium.

The findings bode well for the capability of Webb’s instruments to conduct the broad range of investigations of exoplanets — planets around other stars — hoped for by the science community. That includes probing the atmospheres of smaller, rocky planets like those in the TRAPPIST-1 system.

“We observed the exoplanet with several instruments that together cover a broad swath of the infrared spectrum and a panoply of chemical fingerprints inaccessible until JWST,” said Natalie Batalha, an astronomer at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who contributed to and helped coordinate the new research. “Data like these are a game changer.”

The suite of discoveries is detailed in a set of five new scientific papers, three of which are in press and two of which are under review. Among the unprecedented revelations is the first detection in an exoplanet atmosphere of sulphur dioxide, a molecule produced from chemical reactions triggered by high-energy light from the planet’s parent star. On Earth, the protective ozone layer in the upper atmosphere is created in a similar way.

“This is the first time we have seen concrete evidence of photochemistry — chemical reactions initiated by energetic stellar light — on exoplanets,” said Shang-Min Tsai, a researcher at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom and lead author of the paper explaining the origin of sulphur dioxide in WASP-39 b’s atmosphere. “I see this as a really promising outlook for advancing our understanding of exoplanet atmospheres with [this mission].”

This led to another first: scientists applying computer models of photochemistry to data that require such physics to be fully explained. The resulting improvements in modelling will help build the technological know-how needed to interpret potential signs of habitability in the future.

“Planets are sculpted and transformed by orbiting within the radiation bath of the host star,” Batalha said. “On Earth, those transformations allow life to thrive.”

The planet’s proximity to its host star — eight times closer than Mercury is to our Sun — also makes it a laboratory for studying the effects of radiation from host stars on exoplanets. Better knowledge of the star-planet connection should bring a deeper understanding of how these processes affect the diversity of planets observed in the galaxy.

Other atmospheric constituents detected by the Webb telescope include sodium (Na), potassium (K), and water vapour (H2O), confirming previous space- and ground-based telescope observations as well as finding additional fingerprints of water, at these longer wavelengths, that haven’t been seen before.

Webb also saw carbon dioxide (CO2) at higher resolution, providing twice as much data as reported from its previous observations. Meanwhile, carbon monoxide (CO) was detected, but obvious signatures of both methane (CH4) and hydrogen sulphide (H2S) were absent from the Webb data. If present, these molecules occur at very low levels.

To capture this broad spectrum of WASP-39 b’s atmosphere, an international team numbering in the hundreds independently analysed data from four of the Webb telescope’s finely calibrated instrument modes.

“We had predicted what [the telescope] would show us, but it was more precise, more diverse and more beautiful than I think I actually believed it would be,” said Hannah Wakeford, an astrophysicist at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom who investigates exoplanet atmospheres.

Having such a complete roster of chemical ingredients in an exoplanet atmosphere also gives scientists a glimpse of the abundance of different elements in relation to each other, such as the carbon-to-oxygen or potassium-to-oxygen ratios. That in turn provides insight into how this planet — and perhaps others — formed out of the disc of gas and dust surrounding the parent star in its younger years.

WASP-39 b’s chemical inventory suggests a history of smashups and mergers of smaller bodies called planetesimals to create an eventual goliath of a planet.

“The abundance of sulphur [relative to] hydrogen indicated that the planet presumably experienced significant accretion of planetesimals that can deliver [these ingredients] to the atmosphere,” said Kazumasa Ohno, a UC Santa Cruz exoplanet researcher who worked on Webb data. “The data also indicates that the oxygen is a lot more abundant than the carbon in the atmosphere. This potentially indicates that WASP-39 b originally formed far away from the central star.

By precisely revealing the details of an exoplanet atmosphere, the Webb telescope’s instruments performed well beyond scientists’ expectations — and promise a new phase of exploration of the broad variety of exoplanets in the galaxy.

“We are going to be able to see the big picture of exoplanet atmospheres,” said Laura Flagg, a researcher at Cornell University and a member of the international team. “It is incredibly exciting to know that everything is going to be rewritten. That is one of the best parts of being a scientist.”

More information

Webb is the largest, most powerful telescope ever launched into space. Under an international collaboration agreement, ESA provided the telescope’s launch service, using the Ariane 5 launch vehicle. Working with partners, ESA was responsible for the development and qualification of Ariane 5 adaptations for the Webb mission and for the procurement of the launch service by Arianespace. ESA also provided the workhorse spectrograph NIRSpec and 50% of the mid-infrared instrument MIRI, which was designed and built by a consortium of nationally funded European Institutes (The MIRI European Consortium) in partnership with JPL and the University of Arizona.

Webb is an international partnership between NASA, ESA and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).

Press release from ESA Webb