GW231123: LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA detect most massive black hole merger to date

Gravitational waves from massive black holes challenge current astrophysical models

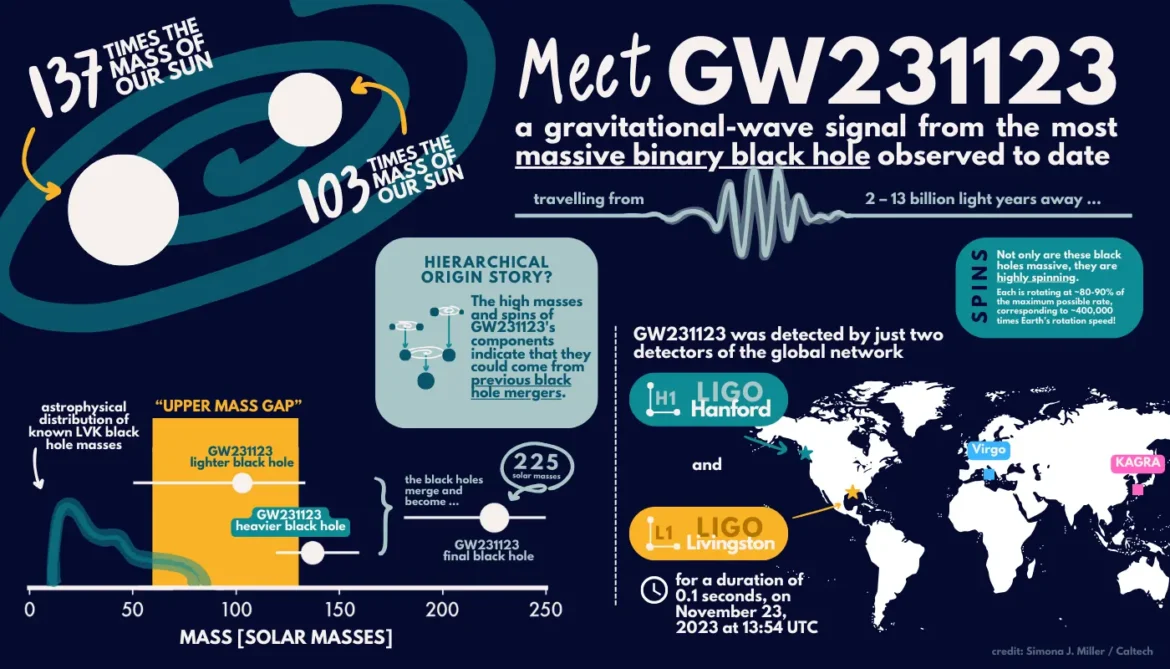

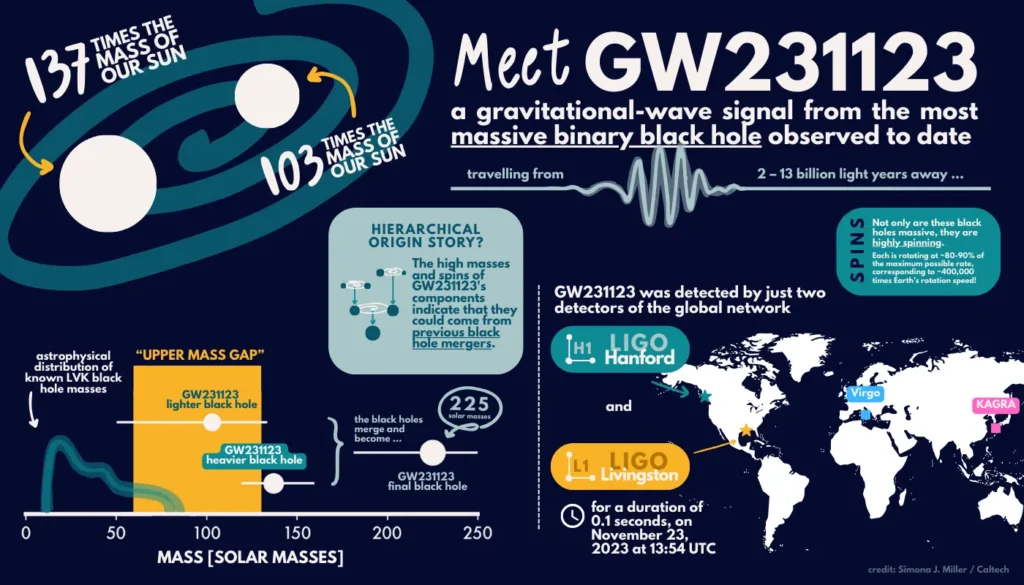

The LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA (LVK) Collaboration has detected the merger of the most massive black holes ever observed with gravitational waves using the US National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded LIGO observatories. The powerful merger produced a final black hole approximately 225 times the mass of our Sun. The signal, designated GW231123, was detected during the fourth observing run of the LVK network on November 23, 2023.

The two black holes that merged were approximately 103 and 137 times the mass of the Sun. In addition to their high masses they are also rapidly spinning, making this a uniquely challenging signal to interpret and suggesting the possibility of a complex formation history.

“The discovery of such a massive and highly spinning system presents a challenge not only to our data analysis techniques – says Ed Porter, researcher at the Astroparticle and Cosmology laboratory (APC) of CNRS in Paris – but will have a major effect on the theoretical studies of black hole formation channels and waveform modelling for many years to come. Actually, current models of stellar evolution do not allow the existence of such massive black holes, which could possibly have formed through previous mergers of smaller black holes.”

Approximately 100 black-hole mergers have previously been observed through gravitational waves, analysed and shared with the wider scientific community. Until now the most massive binary was the source of GW190521, with a much smaller total mass of “only” 140 times that of the sun.

Before now, the most massive black hole merger—produced by an event that took place in 2021 called GW190521—had a total mass of 140 times that of the Sun.

In the more recent GW231123 event, the 225-solar-mass black hole was created by the coalescence of black holes each approximately 100 and 140 times the mass of the Sun.

In addition to their high masses, the black holes are also rapidly spinning.

“This is the most massive black hole binary we’ve observed through gravitational waves, and it presents a real challenge to our understanding of black hole formation,” says Mark Hannam of Cardiff University and a member of the LVK Collaboration. “Black holes this massive are forbidden through standard stellar evolution models. One possibility is that the two black holes in this binary formed through earlier mergers of smaller black holes.”

Dave Reitze, the executive director of LIGO at Caltech, says, “This observation once again demonstrates how gravitational waves are uniquely revealing the fundamental and exotic nature of black holes throughout the universe.”

A record-breaking system

The high mass and extremely rapid spinning of the black holes in GW231123 push the limits of both gravitational-wave detection technology and current theoretical models. Extracting accurate information from the signal required the use of models that account for the intricate dynamics of highly spinning black holes.

“The black holes appear to be spinning very rapidly—near the limit allowed by Einstein’s theory of general relativity,” explains Charlie Hoy of the University of Portsmouth and a member of the LVK. “That makes the signal difficult to model and interpret. It’s an excellent case study for pushing forward the development of our theoretical tools.”

Researchers are continuing to refine their analysis and improve the models used to interpret such extreme events. “It will take years for the community to fully unravel this intricate signal pattern and all its implications,” says Gregorio Carullo of the University of Birmingham and a member of the LVK. “Despite the most likely explanation remaining a black hole merger, more complex scenarios could be the key to deciphering its unexpected features. Exciting times ahead!”

Probing the limits of gravitational-wave astronomy

The high mass and extremely rapid spinning of the black holes in GW231123 pushes the limits of both gravitational-wave detection technology and current theoretical models. Extracting accurate information from the signal required the use of theoretical models that account for the complex dynamics of highly spinning black holes.

“This event pushes our instrumentation and data-analysis capabilities to the edge of what’s currently possible,” says Dr. Sophie Bini, a postdoctoral researcher at Caltech, previously at the University of Trento. “It’s a powerful example of how much we can learn from gravitational-wave astronomy—and how much more there is to uncover.”

Gravitational-wave detectors such as LIGO in the United States, Virgo in Italy, and KAGRA in Japan are designed to measure minute distortions in spacetime caused by violent cosmic events like black hole mergers. The fourth observing run began in May 2023 and observations from the first half of the run (up to January 2024) will be published later in the summer.

“With the longest continuous observation to date and enhanced sensitivity, the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA fourth observing campaign is delivering invaluable new insights into our understanding of the universe –says Viola Sordini, researcher at the Institute of Physics of the 2 Infinities (IP2I) of CNRS in Lyon and deputy spokesperson of the Virgo Collaboration – This exciting discovery opens a new season of results, with many more expected throughout the summer and a continued stream of findings anticipated over the next two years. Publications are followed by release of the data, in support of the broader scientific community and open science”

GW231123 will be presented at the 24th International Conference on General Relativity and Gravitation (GR24) and the 16th Edoardo Amaldi Conference on Gravitational Waves, held jointly as the GR-Amaldi meeting in Glasgow, UK, from July 14-18 2025.

LIGO, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory, made history in 2015 when it made the first-ever direct detection of gravitational waves, ripples in space-time. In that case, the waves emanated from a black hole merger that resulted in a final black hole 62 times the mass of our Sun. The signal was detected jointly by the twin detectors of LIGO, one located in Livingston, Louisiana, and the other in Hanford, Washington.

Since then, the LIGO team has teamed up with partners at the Virgo detector in Italy and KAGRA (Kamioka Gravitational Wave Detector) in Japan to form the LVK Collaboration. These detectors have collectively observed more than 200 black hole mergers in their fourth run, and about 300 in total since the start of the first run in 2015.

The LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA Collaboration

LIGO is funded by the NSF, and operated by Caltech and MIT, which conceived and built the project. Financial support for the Advanced LIGO project was led by NSF with Germany (Max Planck Society), the U.K. (Science and Technology Facilities Council) and Australia (Australian Research Council) making significant commitments and contributions to the project. More than 1,600 scientists from around the world participate in the eQort through the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, which includes the GEO Collaboration. Additional partners are listed at https://my.ligo.org/census.php

The Virgo Collaboration is currently composed of approximately 1.000 members from 175 institutions in 20 different (mainly European) countries. The European Gravitational Observatory (EGO) hosts the Virgo detector near Pisa in Italy, and is funded by Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in France, the National Institute of Nuclear Physics (INFN) in Italy, the National Institute of Subatomic Physics (Nikhef) in the Netherlands, The Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO) e the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research (F.R.S.–FNRS). A list of the Virgo Collaboration groups can be found at: https://www.virgo-gw.eu/about/

KAGRA is the laser interferometer with 3 km arm-length in Kamioka, Gifu, Japan. The host institute is Institute for Cosmic Ray Research (ICRR), the University of Tokyo, and the project is co-hosted by National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) and High Energy Accelerator Research Organization (KEK). KAGRA collaboration is composed of over 400 members from 128 institutes in 17 countries/regions. KAGRA’s information for general audiences is at the website https://gwcenter.icrr.u-tokyo.

Press release from EGO and California Institute of Technology